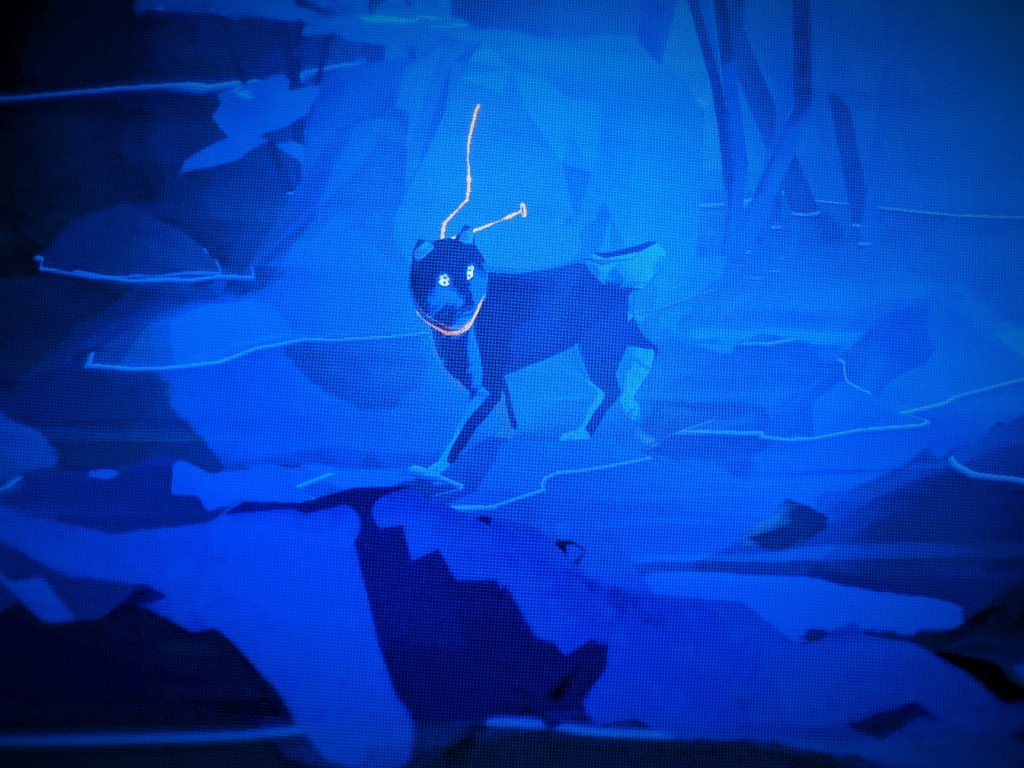

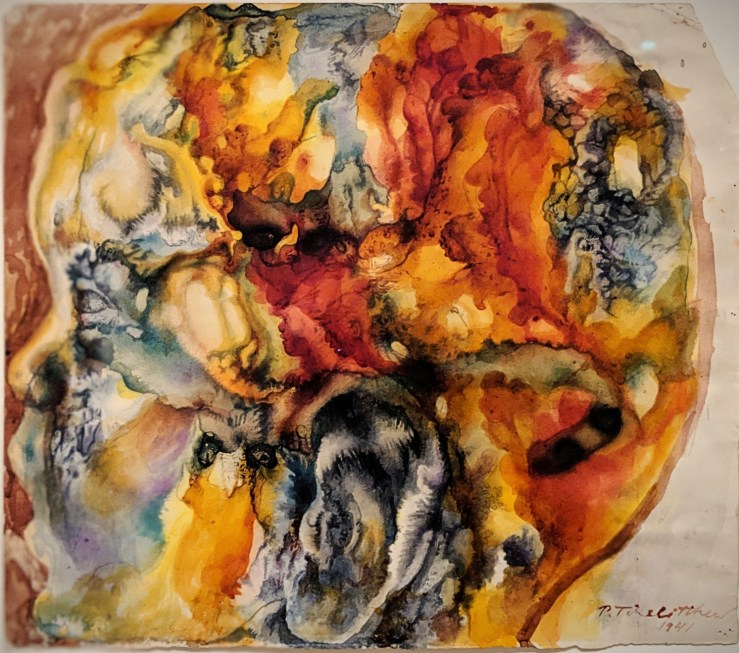

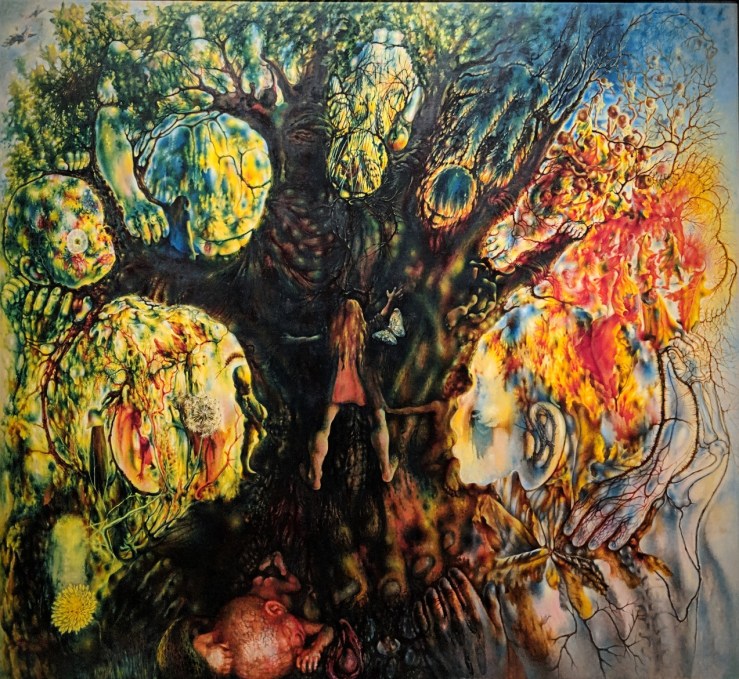

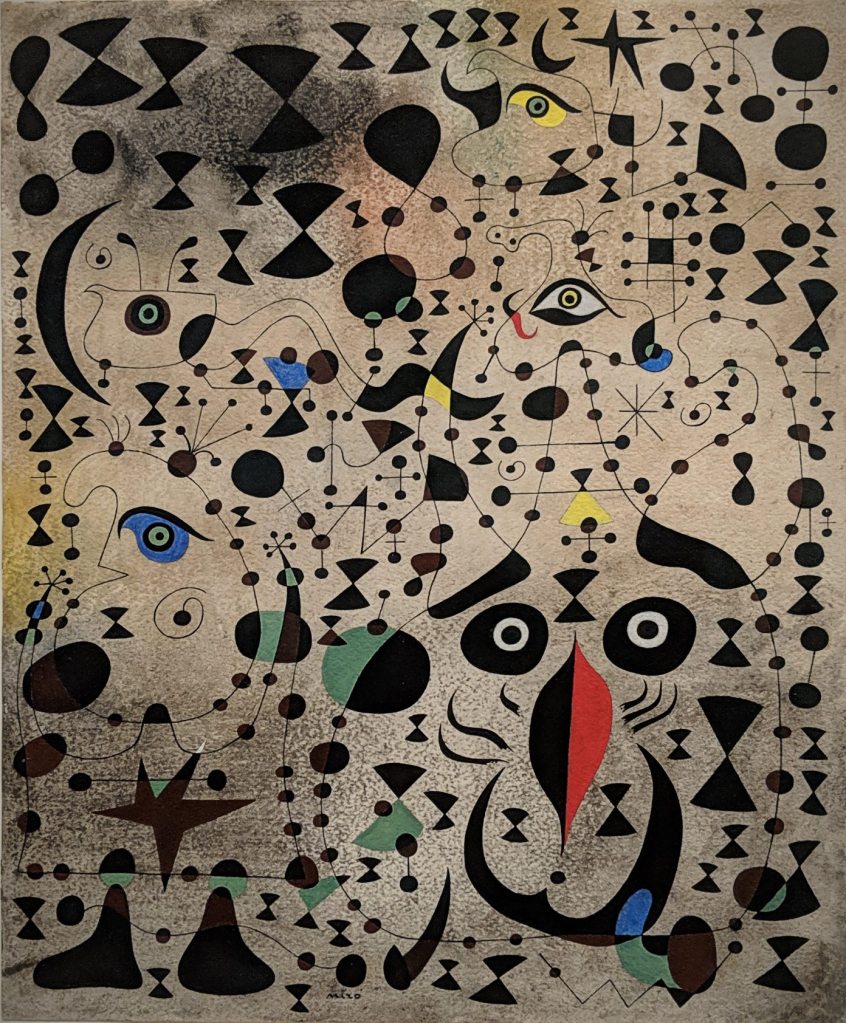

“You and all my writer friends have given me much help and improved my understanding of many things,” Joan Miró told the French poet Michel Leiris in the summer of 1924, writing from his family’s farm in Montroig, a small village nestled between the mountains and the sea in his native Catalonia. The next year, Miró’s intense engagement with poetry, the creative process, and material experimentation inspired him to paint The Birth of the World.

In this signature work, Miró covered the ground of the oversize canvas by applying paint in an astonishing variety of ways that recall poetic chance procedures. He then added a series of pictographic signs that seem less painted than drawn, transforming the broken syntax, constellated space, and dreamlike imagery of avant-garde poetry into a radiantly imaginative and highly inventive form of painting. He would later describe this work as “a sort of genesis,” and his Surrealist poet friends titled it The Birth of the World. [source: MoMA]

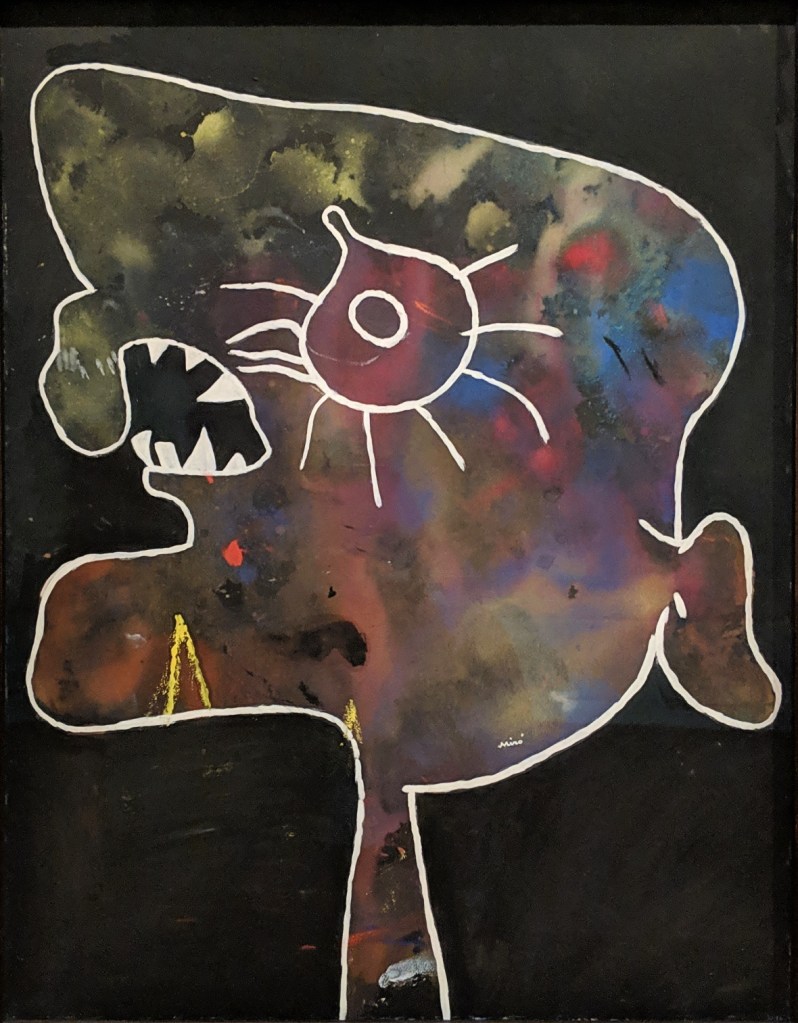

The exhibition ran between February-June 2019 and featured artwork from the Museum of Modern Art’s collection of Miró’s works, which is one of the finest and most comprehensive in the world. However, the most comprehensive selection of Miró’s oeuvre actually on view has to be that of the Fundació Joan Miró, in Barcelona, a dedicated space created by Joan Miró himself with the idea of making art accessible to all.

MoMA, New York City

April 4th, 2019