Mind of the Mound: Critical Mass by Trenton Doyle Hancock

MASS MoCA, North Adams, MA

September 1st, 2019

Mind of the Mound: Critical Mass by Trenton Doyle Hancock

MASS MoCA, North Adams, MA

September 1st, 2019

Colton Worley

Batman

Illustrating Batman: Eighty Years of Comics and Pop Culture

Society of Illustrators, 2019

June 29th, 2019

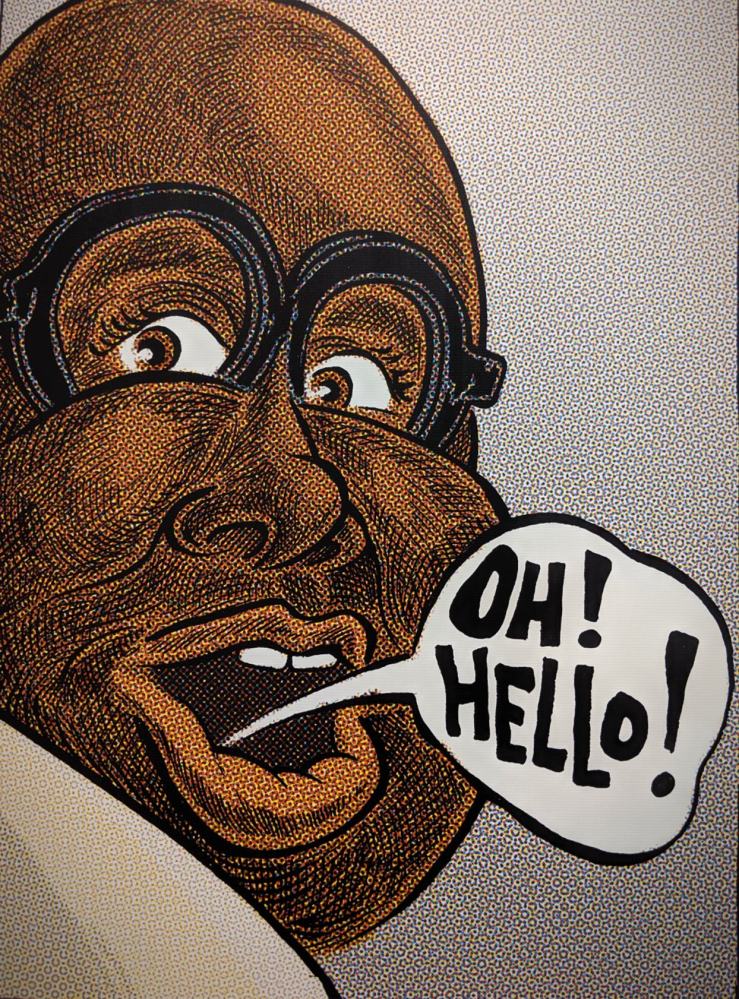

Robert Crumb is an unblinking witness to and graphic critic of the dysfunctional strangeness of the Disunited States. He is peerless in that regard because there’s simply no one like him and no one is as ”far out”. – Robert Storr

Drawing for Print: Mind Fucks, Kultur Klashes, Pulp Fiction & Pulp Fact by the Illustrious R. Crumb

David Zwirner Gallery, New York

March 07th, 2019

Brenda Starr, Reporter debuted in June of 1940 and was an immediate hit with young women and girls. Brenda Starr’s name came from a 1930’s debutante, Brenda Frazier, and her body, fashion sense, and persona mirrored leading Hollywood actress, Rita Hayworth, complete with matching long red hair and a curvaceous figure.

At its peak, Brenda Starr, Reporter was included in 250 newspapers and read by more than 60 million readers. When Starr and her long-time “Mystery Man” boyfriend, whose very survival depended on the serum found in the fictitious but famous black orchid, finally married after 36 years in 1976, President Gerald Ford sent a congratulatory telegram. [source]

Random squares from an exhibition @ The Society of Illustrators

February 9th, 2019

Of all the stars who worked in the golden age of the Hollywood studio system, few valued the acts of looking and being looked at more than Jerry Lewis. Lewis had years of stage experience behind him by the time he emerged as a major screen actor and director, and acknowledging the audience became an essential aspect of the ”comedy of looks” that characterized his work. In no other Lewis film is the experience of being seen so central a theme as it is in The Nutty Professor (1963), in which he treats his audience as a main character. In this adaptation of the Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde story, his masterly dual performance as the self-effacing Professor Kelp and the narcissistic Buddy Love represents different sides of the Lewis persona, while on-screen students and night-club audiences who witness his character’s behaviour represent the critical gaze of the movie-going public.

[source: MoMA]

Bill Avery

Bill Avery

Jerry Lewis shooting a home movie, 1953

Bill Crespinel

Bill Crespinel

Jerry Lewis mixing music at this home, 1961

John Jensen (American, 1924-2003)

John Jensen (American, 1924-2003)

Scenes from the Hangover sequence, 1962

Black and coloured pencil on vellum paper

John Jensen (American, 1924-2003)

John Jensen (American, 1924-2003)

Scenes from the Stella fantasy sequence, 1962

Black and coloured pencil and pastel on vellum paper

John Jensen (American, 1924-2003)

John Jensen (American, 1924-2003)

Mina bird cage sketches, 1962

Pencil on paper

John Lauris Jensen’s storyboards for The Nutty Professor were on display between October 2018 – March 2019; they were a recent gift to the Museum of Modern Art.

John Lauris Jensen’s storyboards for The Nutty Professor were on display between October 2018 – March 2019; they were a recent gift to the Museum of Modern Art.

January 5th, 2019

Original art from the Museum of Illustration

The Scrambled Yeggs by Robert McGinnis

The Scrambled Yeggs by Robert McGinnis

Cover illustration for the story by Richard Prather

Fawcett Gold Medal Books, 1960, 1968

Designers Colours and Casein White on hot press illustration board

Cafe Sinister by Martha Sawyers

Cafe Sinister by Martha Sawyers

Illustration for the story of the same name by Ben Hecht

Caption: ”I noticed a few evenings later that the baron had a different girl with him. ‘Well, we’ve got a new clue,’ I said. ‘We’ve found out the baron has a redhead fetish.”’

Collier’s magazine, August 21, 1943

Pastel

Hail and Farewell by A. Carter

Hail and Farewell by A. Carter

Illustration for the story by Williston Rich

The American Magazine, December 1938

Oil on canvas

The Party Dress by Henry Patrick Raleigh

The Party Dress by Henry Patrick Raleigh

Interior illustration for the serialized novel by Joseph Hergesheimer

Caption: ”Lea cut in on Francis. ‘Against my better judgement,’ he said to Nina, ‘I am obliged to tell you are a sweet affair.’ Nina was in a glow of triumph. What especially engaged her was the fact that men rather than women spoke of her dress and praised it.”’

Hearst’s International combined with Cosmopolitan, November 1929

Ink and watercolour on illustration board

Portrait of Billie Burke by Frederic L. ”Eric” Pape

Portrait of Billie Burke by Frederic L. ”Eric” Pape

Published in the theatre section of the Sunday New York Herald Tribune, advertisement for ”The Truth Game”, December 28, 1930

Litho crayon on paper

Society of Illustrators

July 28th, 2018

So what if I haven’t read any of her stories? Who wouldn’t want to meet Eloise, a mischievous, annoying, adorable little girl, a native New Yawker, and one who lives in the “room on the tippy-top floor” of the Plaza with her Nanny, her dog Weenie and her turtle Skipperdee, at that. So, put on your comfy slacks and your fancy pink flats, and let’s go see what she has in store for us, shall we?

Hilary Knight

Hilary Knight

Study for ”I have a dog that looks like a cat”, 1955

Pen and ink on paper

Hilary Knight

Hilary Knight

After Clayton Knight (1891-1969) and Katharine Sturges Knight (1890-1979)

Cover of The New Yorker, April 17, 1926, 1996

Gouache

Knight’s father, Clayton, specialised in aviation art. A pilot with the British Royal Air Force in World War I, he survived a crash landing in 1918 and went on to illustrate and write numerous books on the history of aviation. Clayton often collaborated with his wife, as in their cover for The New Yorker. Years later, Knight’s colour scheme for Eloise echoed its palette. His hand-painted copy of the cover is an homage to his parents’ work.

Hilary Knight

Hilary Knight

Eloise, 1956

Tempera on paper

A mystery surrounds this Eloise portrait. Painted in 1956 as a birthday gift for Kay Thompson, it vanished from the Plaza Hotel on November 23, 1960, the night of a Junior League debutante ball. ”Eloise kidnapped!” announced Walter Cronkite on CBS Evening News. In spite of Thompson’s offer of a reward, the painted failed to surface.

Two years later, Hilary Knight received a call. A muffled voice told him where his artwork was: in a dumpster, ripped to pieces. Devastated, he retrieved the ruined work and put in a closet.

But the puzzle remained. Who stole Eloise? In retrospect, Thompson herself was the only person who benefited from its disappearance. This may have been the stunt of her career, giving her ample press and a dramatic exit for the character she was done with. Staging a media moment and destroying Knight’s work underlined the primacy of the author’s voice. A final clue came when Thompson confessed in a 1993 interview that she had found the portrait ”on Eight-something Street… torn up.” There’s so much we’ll never know about Kay Thompson – and that’s just how she liked it.

Richard Avedon

Richard Avedon

Kay Thompson, 1951

Photograph

For her session with Richard Avedon, Thompson held a sequinned fan made by Knight. But the had not met yet! D.D. Dixon, Avedon’s assistant for the shoot, had borrowed the prop from Knight, her across-the-hall neighbour. Four years later, Dixon suggested to Thompson that her Eloise voice might make a good book, if she could find the right illustrator. She introduced Knight to Thompson at the Plaza’s Persian Room, in December 1954.

Kay Thompson and Evelyn Rudie, publicity still from the Playhouse 90 movie Eloise, 1956

Kay Thompson and Evelyn Rudie, publicity still from the Playhouse 90 movie Eloise, 1956

Hilary Knight

Hilary Knight

Final illustration for ”I always stay at the National whenever I am in Moscow”, 1959

Pen &brush and ink & graphite on paper

Hilary Knight

Hilary Knight

Final illustration for ”Here’s what we did a lot of”, 1959

Graphite & pen and brush & ink with gouache on paper

A rawther fluzzery picture, don’t you see?

A rawther fluzzery picture, don’t you see?

Hilary Knight

Hilary Knight

Cover illustration for Truman Capote’s manuscript Can a Pig Fly?, 1958

Pen and ink and watercolour on paper

A curious project that never saw publication was Knight’s collaboration with the Truman Capote. The success of Dr. Seuss’ easy reader The Cat in the Hat in 1957 prompted the editors at Random House, its publisher, to ask their entire author list to try this popular new form. None made it to completion, but Knight and Capote enjoyed working together on sketches and notes.

Don Freeman

Don Freeman

Kay Thompson, 1951

Lithograph on paper

Unidentified photographer

Unidentified photographer

Kay Thompson and the Williams Brothers, ca. 1948

Eight songs, forty minutes and no encore. Thompson’s athletic act with the Williams Brothers was innovative, witty, and a smash success. Taking the concept of the overhead boom mike used on movie sets, Thompson had microphones strung all over the ceiling to allow the five performers to move freely about the stage. ”There’d never been an act like it”, Andy Williams said.

Edith Head

Edith Head

Kay Thompson’s office costume for Funny Face, 1956

Pen, ink and watercolour on paper

This meticulously detailed working drawing from Edith Head’s studio documents the cost of Thompson’s office outfit: $480 and another $65 for accessories.

Hilary Knight

Hilary Knight

Sketch for ”I AM ELOISE”, 1996

Watercolour, brush and ink, crayon and graphite on Bristol board

Eloise is the alter ego of cabaret star Kay Thompson (1909–1998), best known for her role as fashion magazine editor in Funny Face (1957), and her collaboration with writer and illustrator Hilary Knight (b. 1926), best known as the Man who Drew Eloise.

These and many more objects, manuscript pages, sketchbooks, portraits, photographs and vintage dolls were on view at the New-York Historical Society, back in 2017. If you missed it fret not. Think Pink and head over to the Plaza. You may just catch a glimpse of the elusive enfant terrible skibbling down the hallway.

New-York Historical Society

September 23rd, 2017

The work of a Polish artist on show at the New-York Historical Society? That seemed strange at first, but a quick read of the introduction shed light on the artist’s relation with the United States and his deep admiration of, and dedication to American democratic values – those same values that are under thread today, shaking American society to its core.

Arthur Szyk fought the demons of WWII in his own creative way, by focusing on political cartooning and producing works that were published as magazine covers, reproduced as posters, and exhibited in art galleries. Among the many admirers of his work during this period was Eleanor Roosevelt, who wrote in her newspaper column My Day: “In its way [Szyk’s work] fights the war against Hitlerism as truly as any of us who cannot actually be on the fighting fronts today.” [source]

Arthur Szyk was so dedicated to American democratic values that he actually became an American citizen in 1948. These are some of the artworks he made during his years in New York City.

FDR’s Soldier in Art, 1944

FDR’s Soldier in Art, 1944

Pencil, watercolour, pen and ink on paper

Szyk’s lively portrait of Franklin Delano Roosevelt (1882-1945) conveyed the artist’s reverence for the US and its principles of freedom and justice, and his belief that the president would lead the Allies – United States, Great Britain and Russia – in defeating the Axis powers. He dedicated the portrait to Eleanor Roosevelt in 1946 following the president’s death. Mrs. Roosevelt admired Szyk and mentioned his artistic crusade in her newspaper columns on several occasions.

We’re running short of Jews!…, 1943

We’re running short of Jews!…, 1943

Ink and graphite on paper

The drawing responded to an announcement made by the World Jewish Congress in November 1942 that confirmed the Nazis’ plan to annihilate Europe’s Jewish population. Szyk later dedicated the drawing to his mother, who died at the Chelmno extermination camp near the Łódź ghetto.

De Profundis. Cain, where is Abel thy Brother?, 1943

De Profundis. Cain, where is Abel thy Brother?, 1943

Ink and graphite on board

Palestine Restricted, 1944

Palestine Restricted, 1944

Pen, ink and pencil on paper

Palestine Restricted furthered Szyk’s condemnation of the White Paper by likening it to a fierce vulture descending on masses of dead and dying men, women and children. The notation, March 31, 1944, marks the date when the British further tightened Jewish immigration, requiring the consent of Palestinian Arabs.

To be shot, as Dangerous Enemies of the Third Reich!, 1943

To be shot, as Dangerous Enemies of the Third Reich!, 1943

Ink and graphite on card

Szyk’s biting depiction of Heinrich Himmler declaring innocent Jewish children as enemies of the Third Reich emphasized the senselessness of Nazi anti-Semitism.

Modern Moses, 1944

Modern Moses, 1944

Pen, ink and pencil on paper

Untitled (The Silent Partner), September 1941

Untitled (The Silent Partner), September 1941

Watercolour, gouache, ink and graphite on paper

Szyk anticipated the US entry into WWII and Hitler’s eventual downfall in this depiction of a decorated figure of Death observing a dangerous poker game between Hitler and ”Ivan”, a pre-Soviet Union Russian leader. Gambling with the fate of the world, Hitler’s cards represent his alliance with Italy, Japan and Vichy France. Ivan’s hand includes the US and Great Britain. Seven puppets, the collaborating leaders of Hungary, Finland, Japan, Italy, Vichy France and Spain, hang from Hitler’s belt. The painting appeared on the cover of Collier’s on November 1, 1941, one month before the US entered the war.

Murder Incorporated: Hirohito, Hitlerhito, Benito, December 1941

Murder Incorporated: Hirohito, Hitlerhito, Benito, December 1941

Watercolour and gouache on paper

Offset lithograph. Here, Szyk characterizes Mussolini, Hirohito and Hitler as venereal diseases, offering perfect incentive to stay healthy and fight in the war effort.

Offset lithograph. Here, Szyk characterizes Mussolini, Hirohito and Hitler as venereal diseases, offering perfect incentive to stay healthy and fight in the war effort.

More than 40 artworks by illustrator and miniaturist Arthur Szyk (1894–1951), were on view at the New-York Historical Society between September 2017 and January 2018.

New-York Historical Society

September 23rd, 2017

There is a sad beauty in these artworks drawing the tragedy of war.

Harry R. Hopps (1869-1937)

Harry R. Hopps (1869-1937)

Destroy This Mad Brute-Enlist, 1917

Colour lithograph

French, early 20th century

French, early 20th century

The Great Nave: Wounded Soldiers Performing Arms Drill at the End of Their Medical Treatment, 1916

Gelatin silver print

During WWI, Paris’ magnificent Grand Palais, a Beaux-Arts structure that opened in 1900 as an exhibition hall, was repurposed as a temporary military hospital that served injured French soldiers. It held one thousand beds and had two operating rooms, as well as an extensive physical rehabilitation centre where soldiers could recover from their injuries, exercise and practice military drills before returning to the front.

John Copley (1875-1950)

John Copley (1875-1950)

Recruits, 1915

Lithograph

Léon Spilliaert (1881-1946)

Léon Spilliaert (1881-1946)

Rockets, 1917

Watercolour, gouache, graphite

Spilliaert served briefly in the Belgian civil guard after the German invasion. A pacifist by nature, he was greatly affected by the violence of war. Here, he depicts a deep blue sky illuminated by the flare of rockets, an image witnessed by both soldiers and civilians in occupied territories. The artist concentrated not on the rockets’ violent potential but on the graceful forms they generate and their resemblance to stars and comets.

French, 20th century

French, 20th century

After the Victory (Au Lendemain de la Victoire), 1918

Printed by Imprimerie Kapp

Published by Librairie Hachette & Co.

Colour lithograph

Many children lost loved ones to the war and were traumatized by the sounds and sights of combat. Ostensibly, celebrating victory, this book, like much wartime propaganda for children, reflects these dark events. Its interior presents images of rebuilding: each page shows a scene of destruction, but when a flap is raised, it shows the same site restored.

Käthe Kollwitz (1867-1945)

Käthe Kollwitz (1867-1945)

The Parents (Die Eltern), from War (Krieg), 1921-22

Printed by Fritz Voigt, Berlin

Woodcut

”Pain,” Kollwitz noted, ”is totally dark.” This raw images portrays the profound grief of parents who, like the artist, lost a child to war. Kollwitz began working in this medium after seeing an exhibition of woodcuts by Ernst Barlach and being inspired by their graphic power; the War series is considered her most important in the technique. Kollwitz spent fifteen years working on a sculpture based on this print. The Grieving Parents, located in the cemetery for German soldiers in western Belgium where her son Peter is buried, is composed of two separate sculptures, showing the parents isolated in their despair.

George Grosz (1893-1959)

George Grosz (1893-1959)

Background (Hintergrund), 1928

3 out of 17 photolithographs with printed portfolio

Käthe Kollwitz (1867-1945)

Käthe Kollwitz (1867-1945)

Mothers (Muetter), from War (Krieg), 1919

Lithograph

In Mothers, women and children huddle together, their linked bodies forming a solid structure that fills the composition. Kollwitz drew herself in the centre, eyes closed and arms wrapped protectively around her two sons: Hans, the elder, and Peter, who was killed in combat at eighteen.

Images from ”World War I and the Visual Arts”, an exhibition exploring ”the myriad and often contradictory ways in which artists responded to the first modern war”.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art

August 6th, 2017

In five scratchboard illustrations and one gouache.

In his 35-year career, Virgil Finlay produced over 2,600 illustrations, a remarkable achievement considering his labor-intensive and time-consuming drawing style.

”Instead of the typical pen and ink or carbon pencil drawings produced by most pulp illustrators, Finlay used a unique technique combining scratchboard—in which a clay-covered board is coated with black ink and the artist scratches away white lines from the black using a sharp blade—with intricate pen cross-hatching and an astonishingly painstaking method of creating tones called stipple.

Contrasted with hatching, or crossed lines, stippling is a time-consuming process in which tones are created with hundreds of tiny individual dots, carefully placed and dripped off the end of an ultra-fine dip pen, one dot at time.” [source] Face in the Abyss

Face in the Abyss

Gouache on illustration board

Appeared on the cover of Famous Fantastic Mysteries magazine for ”Face in the Abyss” by A. Merritt, Frank A. Munsey Co., October 1940

”He came out of his coma. We left a sketch pad and pencils by the bed. He did a drawing, he went back into the coma, and died.”– Lail Finlay, Virgil Finlay’s daughter

Three Against the Stars

Three Against the Stars

Scratchboard, pen and ink

Interior illustration in Fantastic Novels Magazine for ”Three Against the Stars”, by Eric North, New Publications, Inc., May 1950

The Lovers

The Lovers

Scratchboard, pen and ink

Appeared in Startling Stories magazine for ”The Lovers” by Philip José Farmer, Better Publications, August 1952

For the first time in science fiction history an Earth man and an alien woman have a sexual love affair in Philip José Farmer’s ”The Lovers”. This was quite groundbreaking yet controversial in 1950s American pop culture; however, it would seem quite tame compared to today’s science fiction books and films.

Woman reclining in lunar landscape, c. 1955

Woman reclining in lunar landscape, c. 1955

Scratchboard, pen and ink

Conquest of the Moon Pool

Conquest of the Moon Pool

Scratchboard, pen and ink

Interior illustration in Fantastic Novels magazine for ”Conquest of the Moon Pool” by A. Merritt, New Publications, September 1948

From ”Conquest of the Moon Pool”:

”… and suddenly there before us stood two figures! One was a girl – a girl whose eyes were golden… whose softly curved lips were red as the royal coral and whose golden-brown hair reached to her knees! And the second was a gigantic frog – a woman frog… six feet high if an inch and with one webbed paw of its short, powerfully muscled forelegs resting upon the white should of the golden-eyed girl!”

Lur the Witch Woman with Her Consorts, Dwellers in the Mirage

Lur the Witch Woman with Her Consorts, Dwellers in the Mirage

Scratchboard, pen and ink

Appeared on the cover of Fantastic Novels for ”Dwellers in the Mirage”, written by A. Merritt, Frank A. Munsey Co., NY, April 1941

”Dwellers in the Mirage” introduction:

”The strangest adventure any man had encountered since time began faced Leif Langdon when he tumbled through that Alaskan mirage into a lost world.”

Adenturer Leif Langdon stumbles upon an uncommonly warm, hidden Arctic valley where he finds and falls in love with Evalie. Also in this valley are the Little People – elfin warriors fighting against Lur the Witch Woman and her demon riders who raid the Little People’s land for sacrifices to Kraken, their dark lord. Tapping into buried memories of another lifetime, Langdon realizes he had a past life as Kraken and as Lur’s lover. So begins Langdon’s inner struggle between his two selves.

All artwork by Virgil Finlay (1914 – 1971), photographed at the Society of Illustrators

August 15th, 2017

subjective worldview

Actor, writer, cook and author

Travel inspiration & tips to explore Strasbourg

Writer

joy, happiness, travel, adventure, gratitude

"Rêve onirique & Bulle d'évasion"

makes pretty things on paper

This WordPress.com site is Pacific War era information

Welcome to my curious world of words....

Photographs, music and writing about daily life. Contact: elcheo@swcp.com

Free listening and free download (mp3) chill and down tempo music (album compilation ep single) for free (usually name your price). Full merged styles: trip-hop electro chill-hop instrumental hip-hop ambient lo-fi boombap beatmaking turntablism indie psy dub step d'n'b reggae wave sainte-pop rock alternative cinematic organic classical world jazz soul groove funk balkan .... Discover lots of underground and emerging artists from around the world.

A 365 analogue photography project

Barcelona's Multiverse | Art | Culture | Science

Een digitaal atelier aan de (zee)slag.

‘Doodling Ambiguity’s in Ink.’

Miscellaneous photography

Glimpses along the way on a journey of discovery into symmetry...