The sad, whatthehellamIdoingIdon’tbelonghere look in Pink Panther’s eyes when they locked with Magritte’s Portrait.

Jeff Koons || Pink Panther, 1988

René Magritte || The Portrait, 1935

MoMA, New York

February 7th, 2020

The sad, whatthehellamIdoingIdon’tbelonghere look in Pink Panther’s eyes when they locked with Magritte’s Portrait.

MoMA, New York

February 7th, 2020

MoMA, New York

February 7th, 2020

Reaping the benefit of having MoMA at walking distance between home & work.

”After setting up her own photography studio in 1894, in Washington, D.C., Frances Benjamin Johnston was described by The Washington Times as “the only lady in the business of photography in the city.” Considered to be one of the first female press photographers in the United States, she took pictures of news events and architecture and made portraits of political and social leaders for over five decades.

In 1899, the principal of the Hampton Normal and Agricultural Institute in Virginia commissioned Johnston to take photographs at the school for the 1900 Exposition Universelle in Paris. The Hampton Institute was a preparatory and trade school dedicated to preparing African American and Native American students for professional careers. Johnston took more than 150 photographs and exhibited them in the Exposition Nègres d’Amerique (American Negro Exhibit) pavilion, which was meant to showcase improving race relations in America. The series won the grand prize and was lauded by both the public and the press.

Years later, writer and philanthropist Lincoln Kirstein discovered a leather-bound album of Johnston’s Hampton Institute photographs. He gave the album to The Museum of Modern Art, which reproduced 44 of its original 159 photographs in a book called The Hampton Album, published in 1966.” [source]

February 7th, 2020

I think we can all use a booster

MoMA New York

December 8th, 2019

The new MoMA had recently reopened after a four month closure, the last phase of a multimillion dollar expansion and renovation, and it was high time we explored all that extra space. These are a few of my favourite things:

MoMA New York

December 8th, 2019

You just have to wonder: which part in this painting is responsible for the lions’ bewildered expressions? Is it the shock of the nude? The shrill tone of the flute? Am I, the spectator, that scary?

The Dream, 1910 || Henri Rousseau || Oil on canvas

“Entirely self-taught, Henri Rousseau worked a day job as a customs inspector until, around 1885, he retired on a tiny pension to pursue a career as an artist. Without leaving his native France, he made numerous paintings of fantastical jungle landscapes, like the one that fills The Dream.

Living in Paris, he had ready access to images of faraway people and places through popular literature, world expositions, museums, and the Paris Zoo. His visits to the city’s natural history museum and to Jardin des plantes (a combined zoo and botanical garden) inspired the lush jungle, wild animals, and mysterious horn player featured in The Dream. “When I am in these hothouses and see the strange plants from exotic lands, it seems to me that I am entering a dream,” he once said.

The nude woman reclining on a sofa seems to have been lifted from a Paris living room and grafted into this moonlit jungle scene. Her incongruous presence heightens its dreamlike quality and suggests that perhaps the jungle is a projection of her mind, much as it is a projection of Rousseau’s imagination.” [source: MoMA]

June 16th, 2019

Jennifer Bartlett

Rhapsody, 1975-76

When Rhapsody was first shown, in 1976, it occupied the entirety of the art dealer Paula Cooper’s Manhattan gallery space. Consisting of 987 one-foot-square steel panels covering an expanse of more than 150 feet, the work has an overall monumentality, but its small panels invite intimate interaction. Together they represent Bartlett’s attempt to create a painting “that had everything in it,” she has said.

Each of Rhapsody’s steel panels was baked with white enamel, silkscreened, and then painted. Its range of imagery—from photographic images to abstract shapes—presents a variety that undermines any sense of stylistic unity. “It was supposed to be like a conversation,” the artist has explained, “in which people digress from one thing and maybe come back to the subject, then do the same with the next thing.” Looking at Rhapsody is like listening in on this conversation. A viewer can step back and see the ebbs and flows, or come in close and engage deeply with a single topic, sentence, or line. [Source: MoMA]

June 16th, 2019

“You and all my writer friends have given me much help and improved my understanding of many things,” Joan Miró told the French poet Michel Leiris in the summer of 1924, writing from his family’s farm in Montroig, a small village nestled between the mountains and the sea in his native Catalonia. The next year, Miró’s intense engagement with poetry, the creative process, and material experimentation inspired him to paint The Birth of the World.

In this signature work, Miró covered the ground of the oversize canvas by applying paint in an astonishing variety of ways that recall poetic chance procedures. He then added a series of pictographic signs that seem less painted than drawn, transforming the broken syntax, constellated space, and dreamlike imagery of avant-garde poetry into a radiantly imaginative and highly inventive form of painting. He would later describe this work as “a sort of genesis,” and his Surrealist poet friends titled it The Birth of the World. [source: MoMA]

The exhibition ran between February-June 2019 and featured artwork from the Museum of Modern Art’s collection of Miró’s works, which is one of the finest and most comprehensive in the world. However, the most comprehensive selection of Miró’s oeuvre actually on view has to be that of the Fundació Joan Miró, in Barcelona, a dedicated space created by Joan Miró himself with the idea of making art accessible to all.

MoMA, New York City

April 4th, 2019

Colour palleting with:

A Gallery Visitor

Sophie Taeuber-Arp

Dada Head, 1920

Painted wood with glass beads on wire

Salvador Dalí

Retrospective Bust of a Woman, 1933

(some elements reconstructed 1970)

Painted porcelain, bread, corn, feathers, paint on paper, beads, ink stand, sand, and two pens

@MoMA

April 4th, 2019

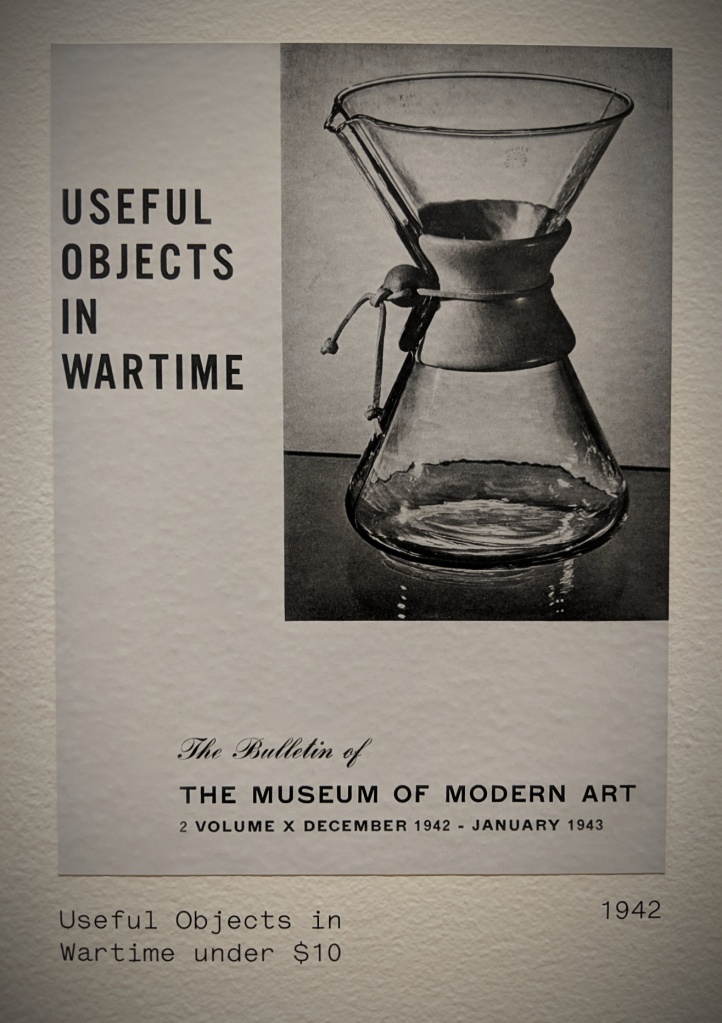

Elevating the functional to a timeless work of art.

“Is there art in a broomstick? Yes, says Manhattan’s Museum of Modern Art, if it is designed both for usefulness and good looks.” This quote, from a 1953 Time magazine review of one of MoMA’s mid-century Good Design exhibitions, gets to the heart of a question the Museum has been asking since its inception: What is good design and how can it enhance everyday life?

Featuring objects from domestic furnishings and appliances to ceramics, glass, electronics, transport design, sporting goods, toys, and graphics, The Value of Good Design explored the democratizing potential of design, beginning with MoMA’s Good Design initiatives from the late 1930s through the 1950s, which championed well-designed, affordable contemporary products. [source: MoMA]

The Value of Good Design

Feb 10–Jun 15, 2019

MoMA

April 4th, 2019

subjective worldview

Actor, writer, cook and author

Travel inspiration & tips to explore Strasbourg

Writer

joy, happiness, travel, adventure, gratitude

"Rêve onirique & Bulle d'évasion"

makes pretty things on paper

This WordPress.com site is Pacific War era information

Welcome to my curious world of words....

Photographs, music and writing about daily life. Contact: elcheo@swcp.com

Free listening and free download (mp3) chill and down tempo music (album compilation ep single) for free (usually name your price). Full merged styles: trip-hop electro chill-hop instrumental hip-hop ambient lo-fi boombap beatmaking turntablism indie psy dub step d'n'b reggae wave sainte-pop rock alternative cinematic organic classical world jazz soul groove funk balkan .... Discover lots of underground and emerging artists from around the world.

A 365 analogue photography project

Barcelona's Multiverse | Art | Culture | Science

Een digitaal atelier aan de (zee)slag.

‘Doodling Ambiguity’s in Ink.’

Miscellaneous photography

Glimpses along the way on a journey of discovery into symmetry...