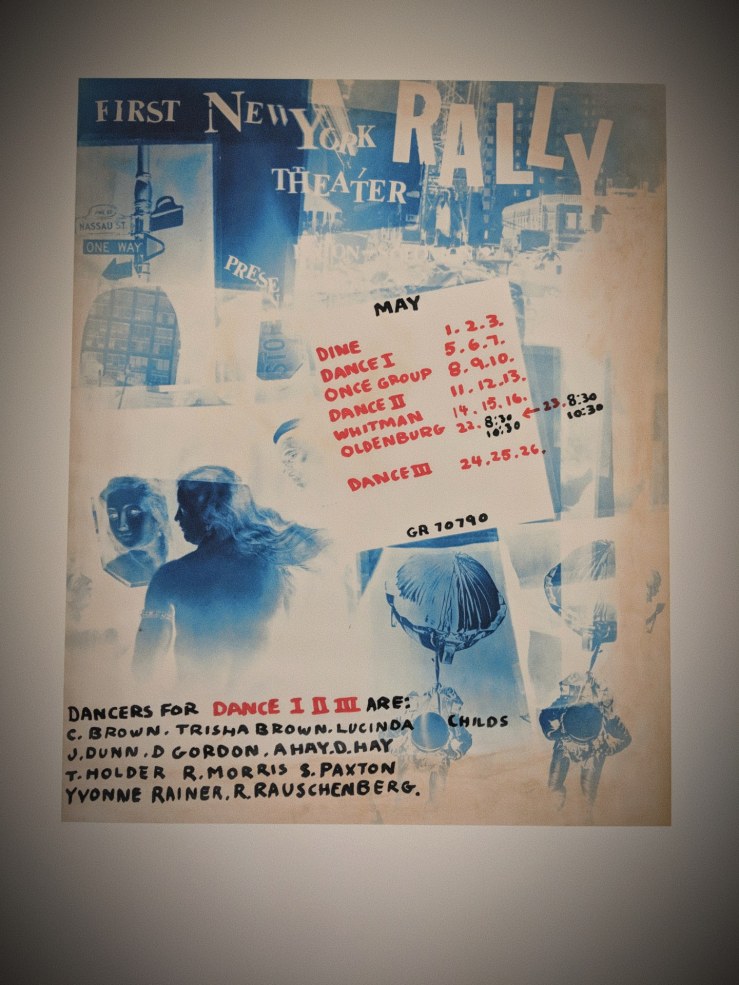

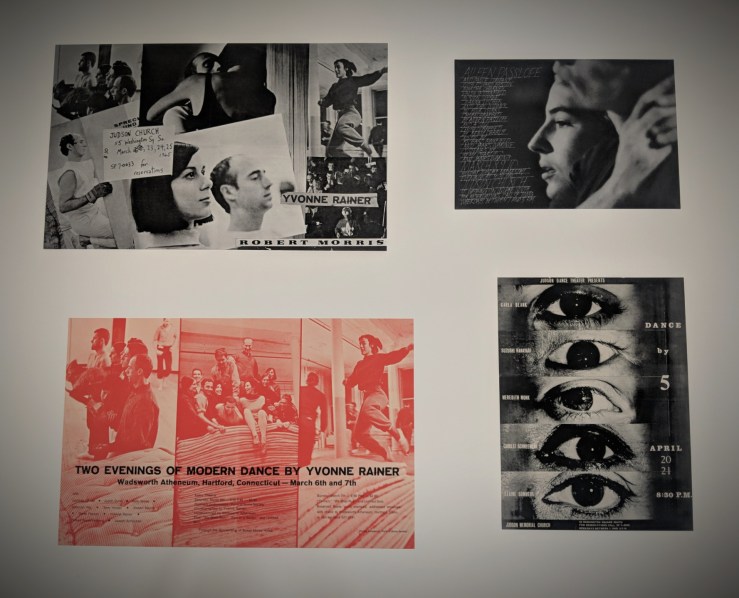

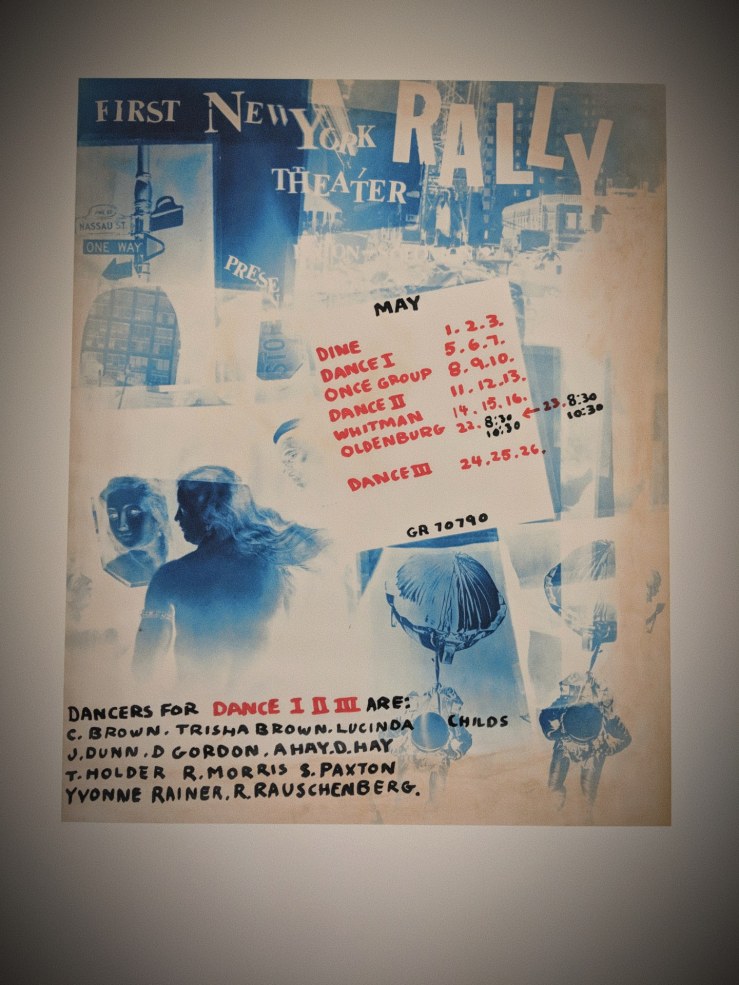

”For a brief period in the early 1960s, a group of choreographers, visual artists, composers, and filmmakers gathered in Judson Memorial Church, a socially engaged Protestant congregation in New York’s Greenwich Village, for a series of workshops that ultimately redefined what counted as dance. The performances that evolved from these workshops incorporated everyday movements—gestures drawn from the street or the home; their structures were based on games, simple tasks, and social dances. Spontaneity and unconventional methods of composition were emphasized. The Judson artists investigated the very fundamentals of choreography, stripping dance of its theatrical conventions, and the result, according to Village Voice critic Jill Johnston, was the most exciting new dance in a generation.” – [source: MoMA]

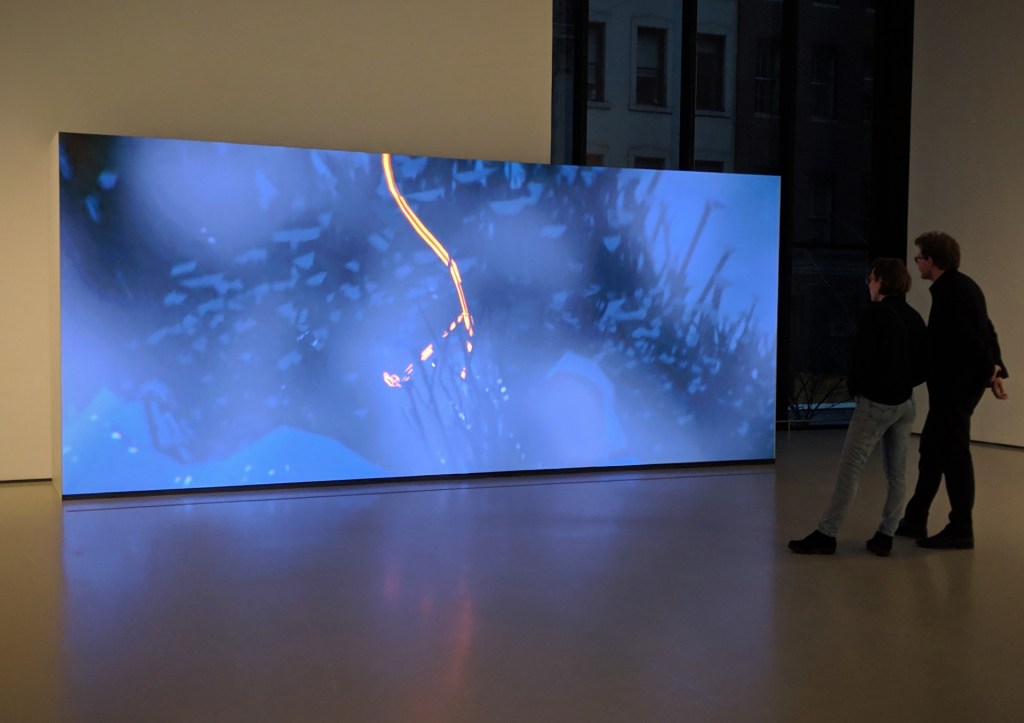

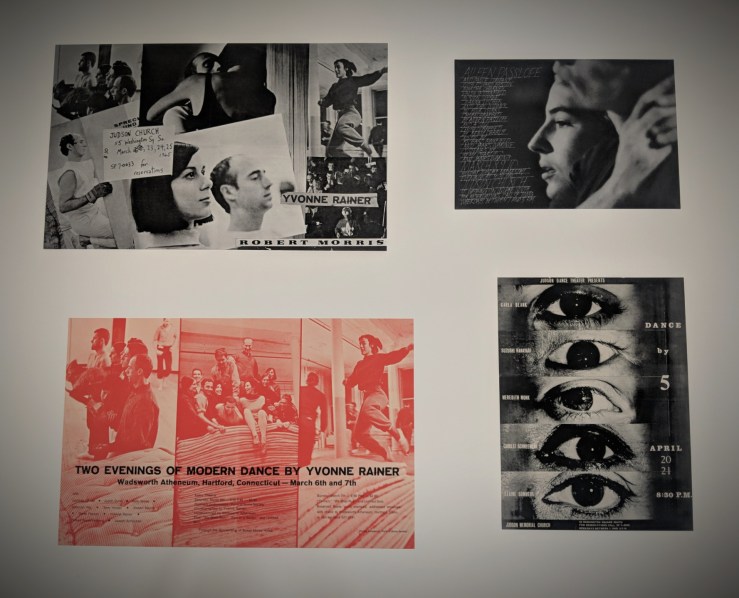

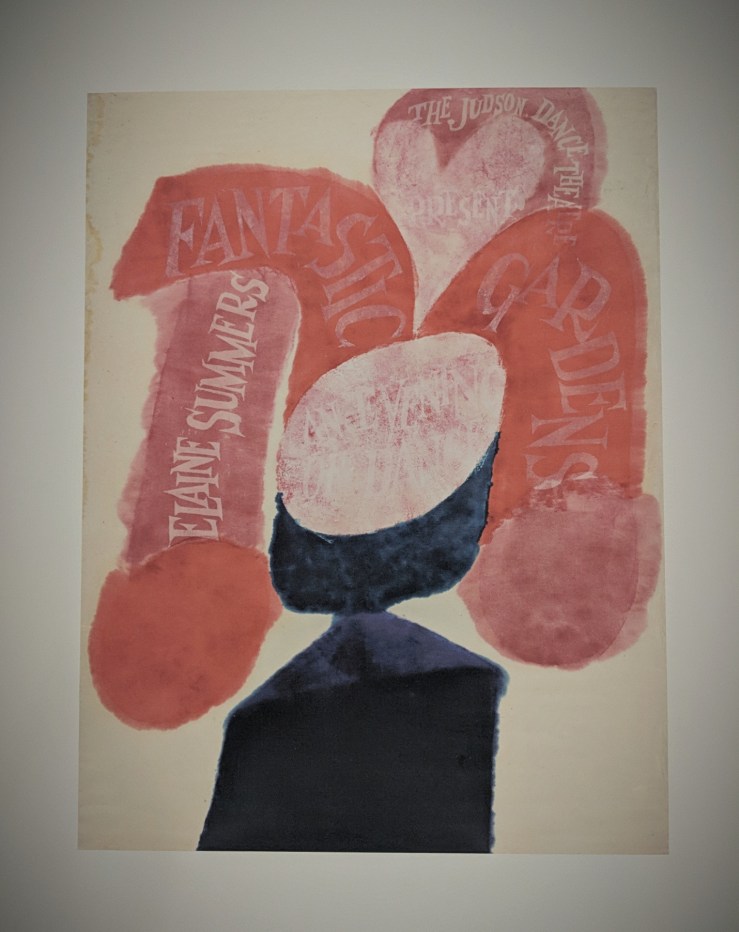

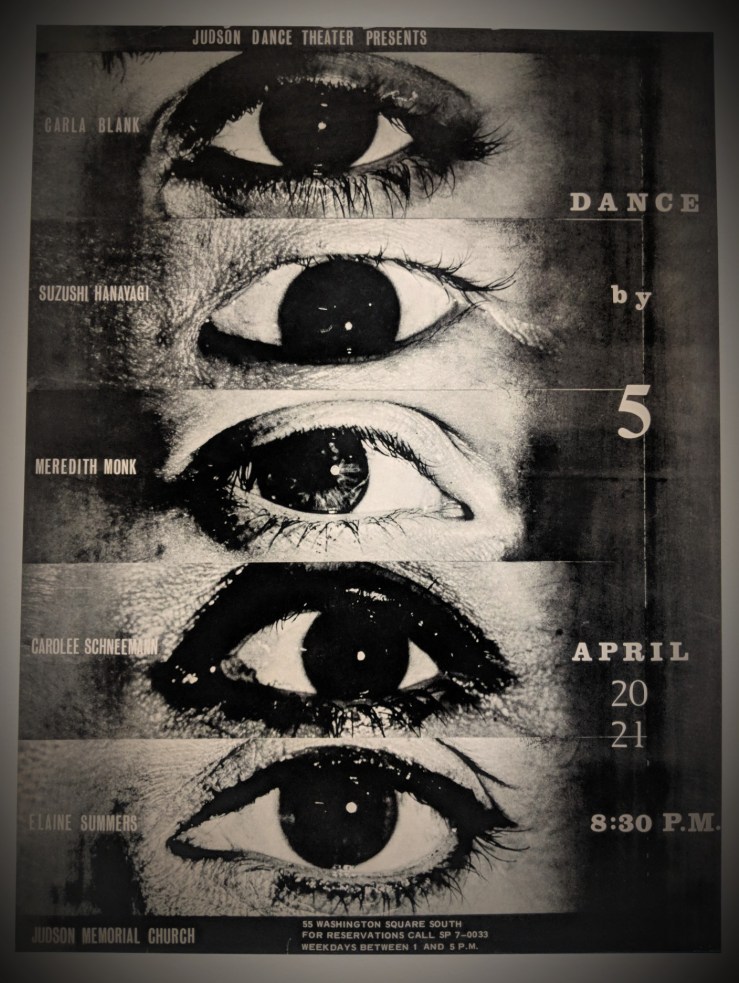

Judson Dance Theater: The Work Is Never Done was a walk through the history of Judson Dance Theater with performances, films, photographs, posters and other archival materials. It was also an introduction to the very beginnings of the life and work of artists I have been admiring for some time – and others that were completely new to me.

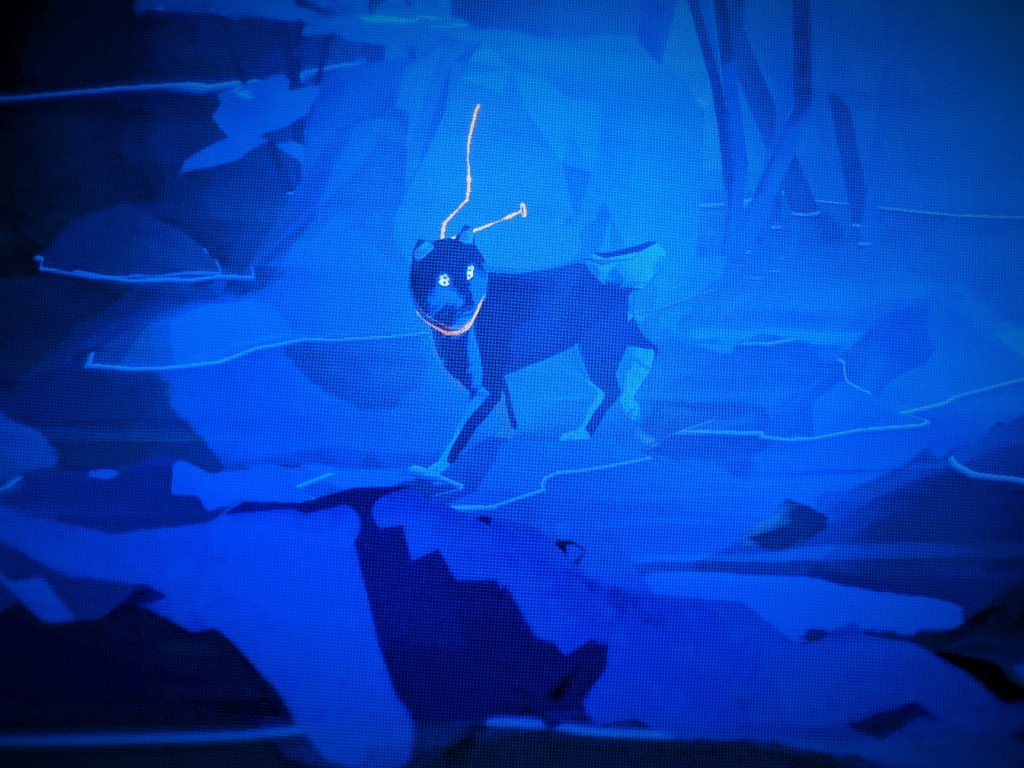

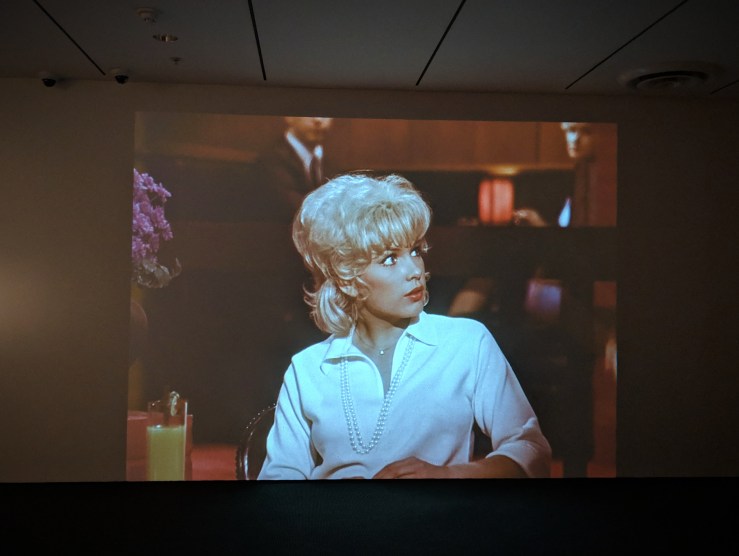

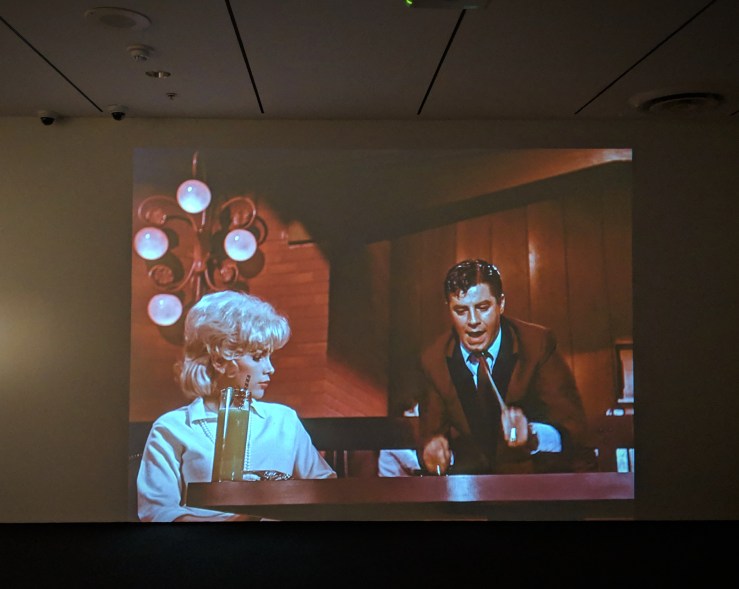

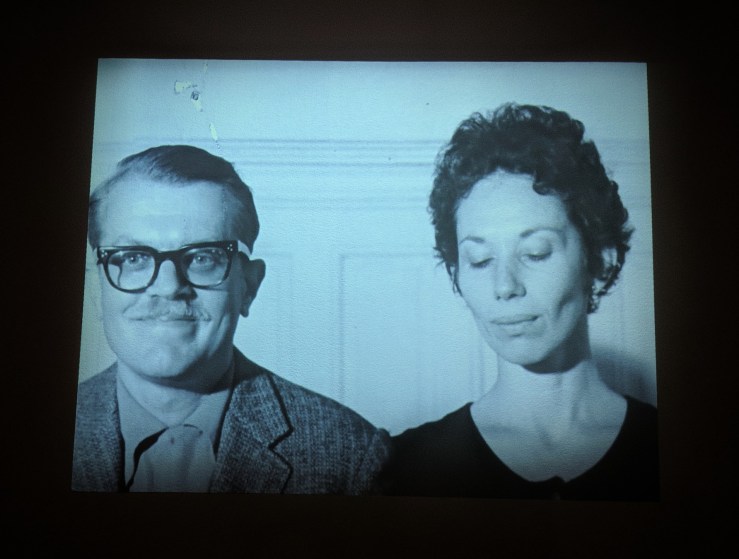

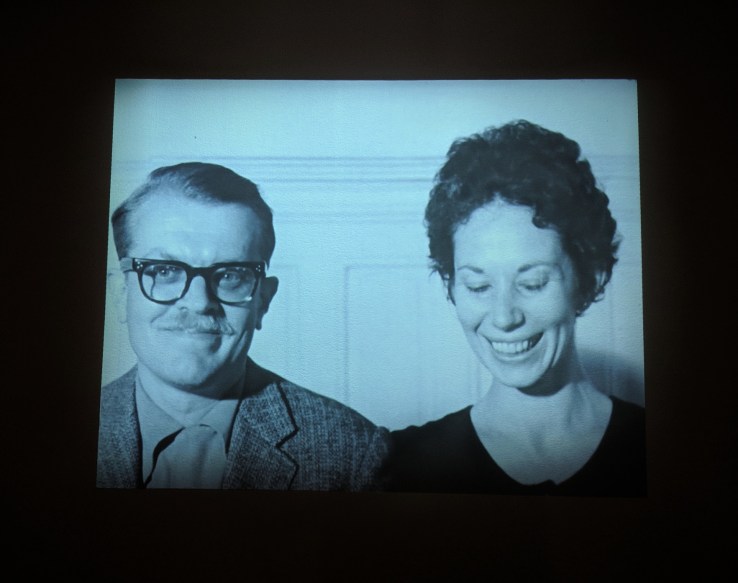

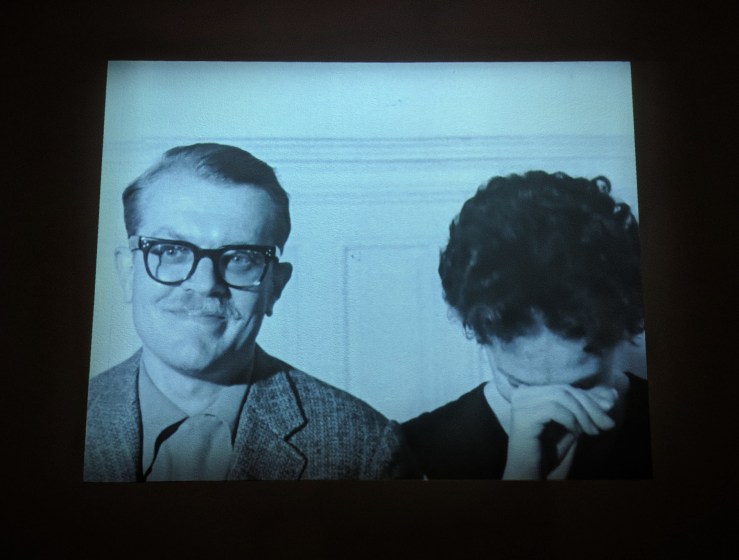

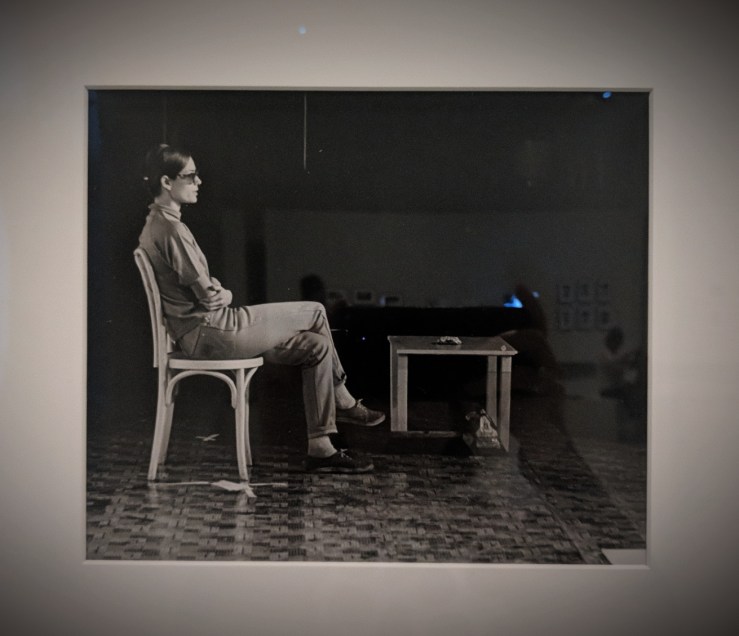

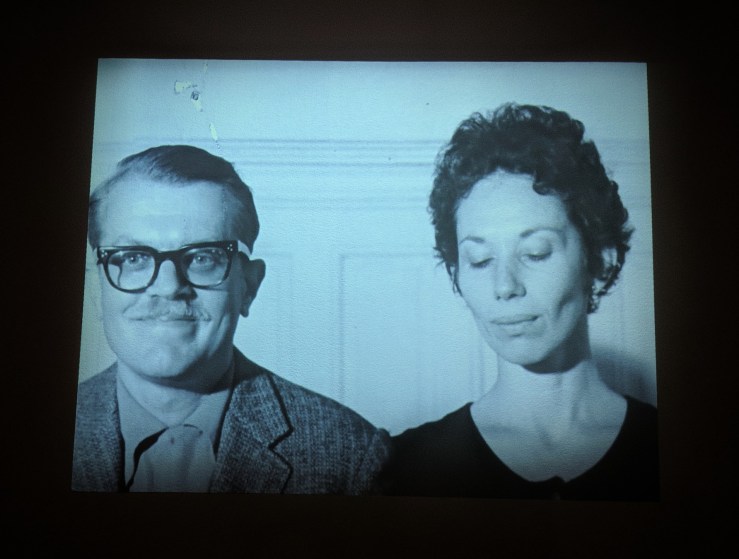

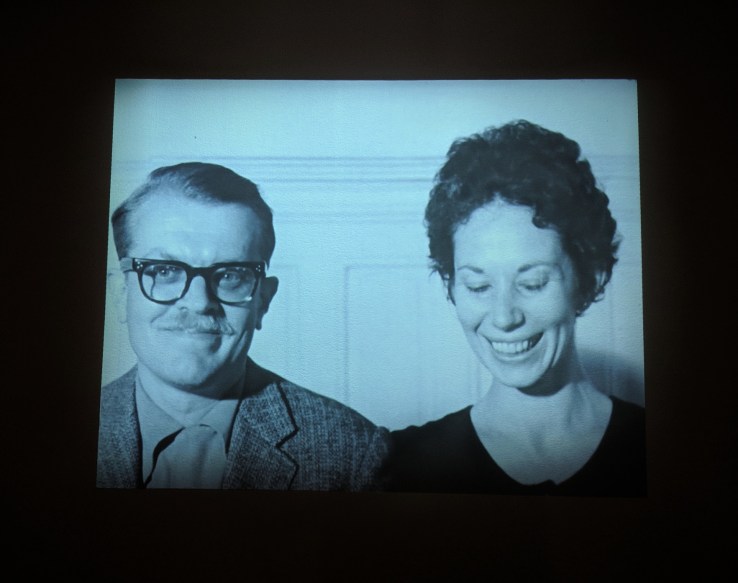

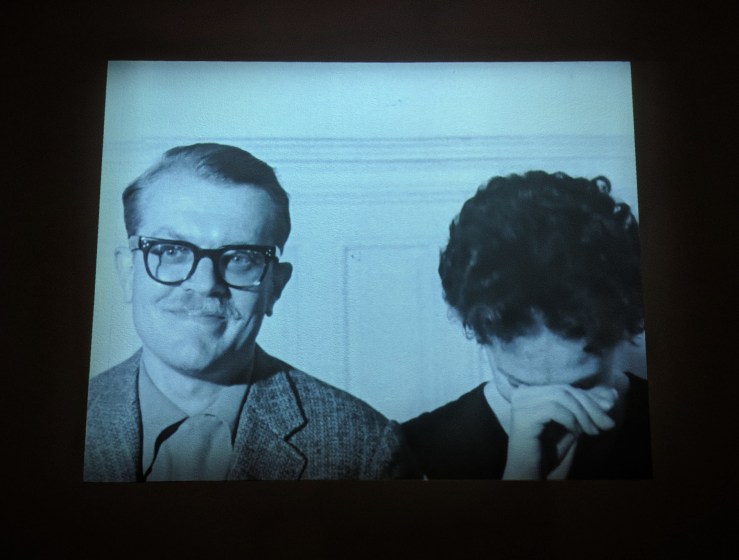

Instructed by the filmmaker Gene Friedman not to talk or hide their faces, Judith Dunn and Robert Ellis Dunn looked directly at the camera with deadpan expressions until they both broke into laughter. Judith Dunn was a choreographer and member of Merce Cunningham’s company, while Robert Dunn was a teacher and Cunningham’s accompanist.

Instructed by the filmmaker Gene Friedman not to talk or hide their faces, Judith Dunn and Robert Ellis Dunn looked directly at the camera with deadpan expressions until they both broke into laughter. Judith Dunn was a choreographer and member of Merce Cunningham’s company, while Robert Dunn was a teacher and Cunningham’s accompanist.

Gene Friedman

Excerpt from Heads, 1965

16mm film transferred to video

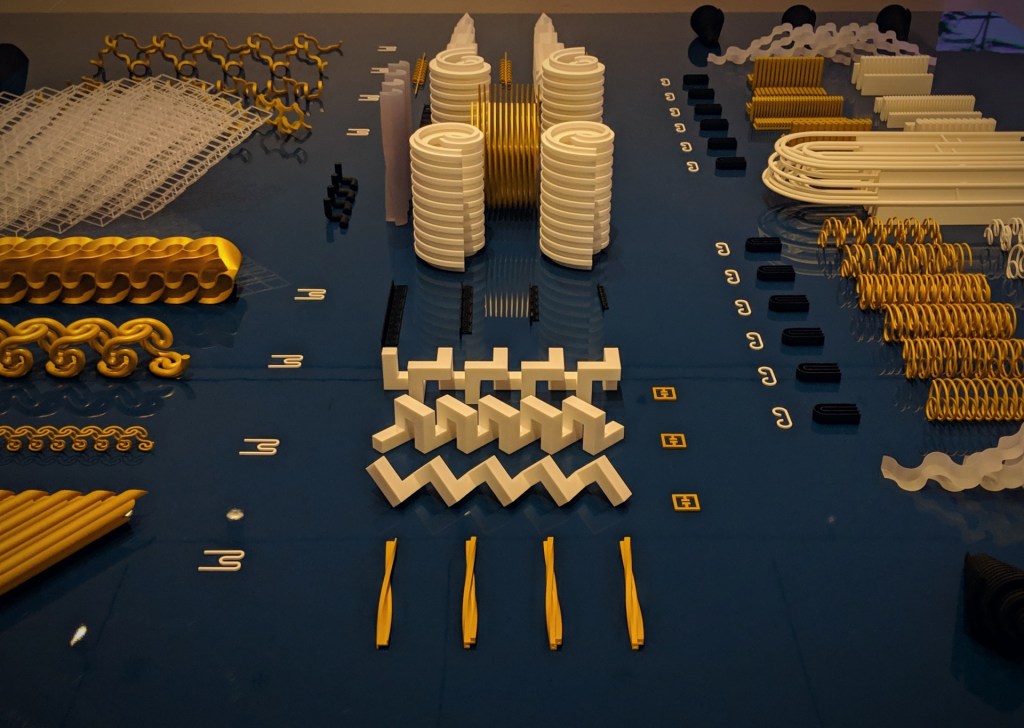

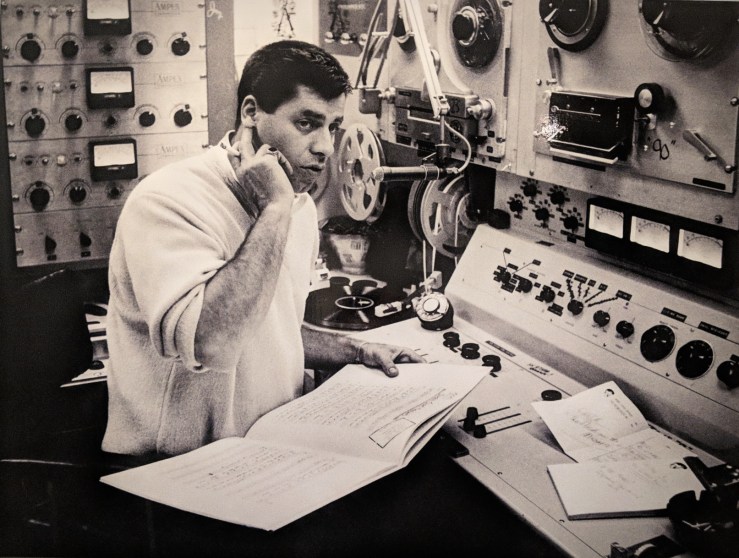

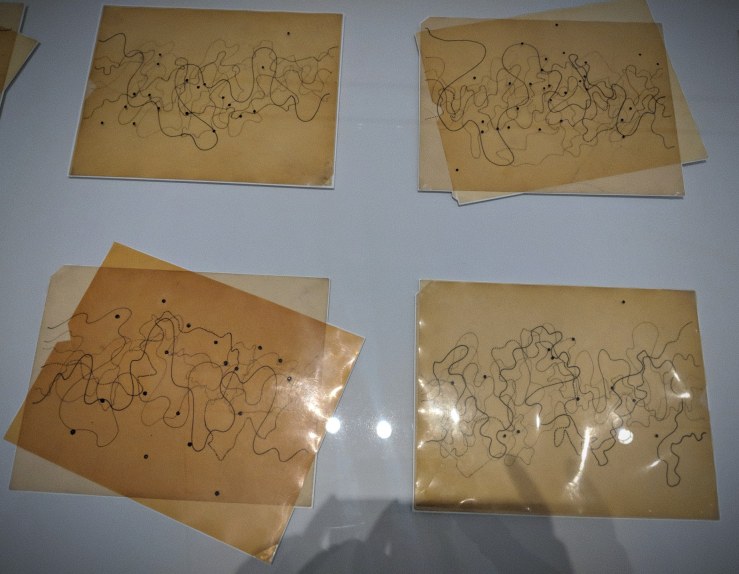

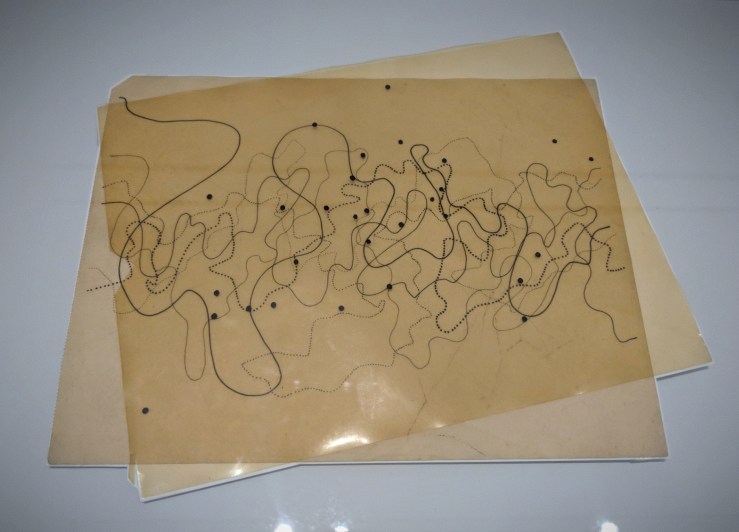

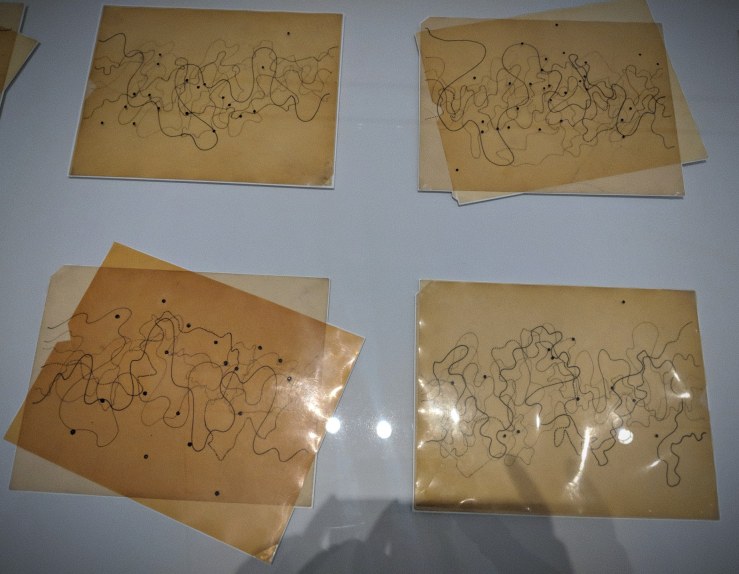

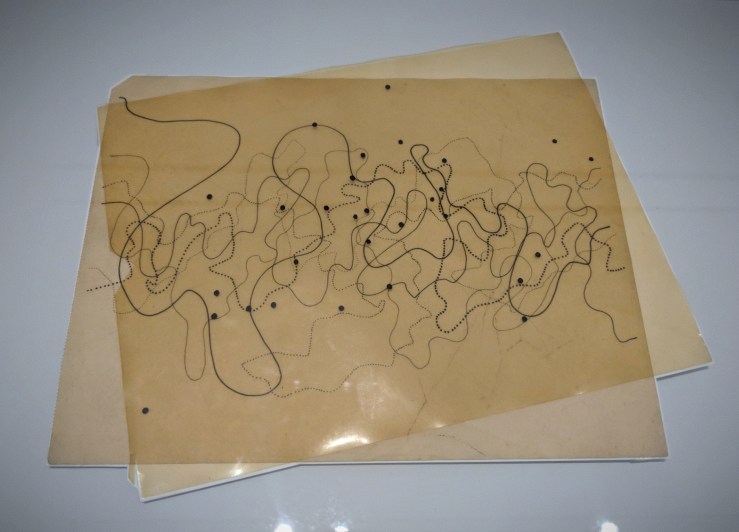

In his workshops, Robert Ellis Dunn presented his students with Cage’s score for ”Fontana Mix” and asked them to use it as inspiration for a performance. The score instructed performers to layer transparencies containing lines and dots over a grid to create a random visual arrangement, with they then interpreted using a variety of movements and actions. This exercise exposed the students to chance operations, a composition technique popularized by Cage that introduced randomness into the art-making process.

In his workshops, Robert Ellis Dunn presented his students with Cage’s score for ”Fontana Mix” and asked them to use it as inspiration for a performance. The score instructed performers to layer transparencies containing lines and dots over a grid to create a random visual arrangement, with they then interpreted using a variety of movements and actions. This exercise exposed the students to chance operations, a composition technique popularized by Cage that introduced randomness into the art-making process.

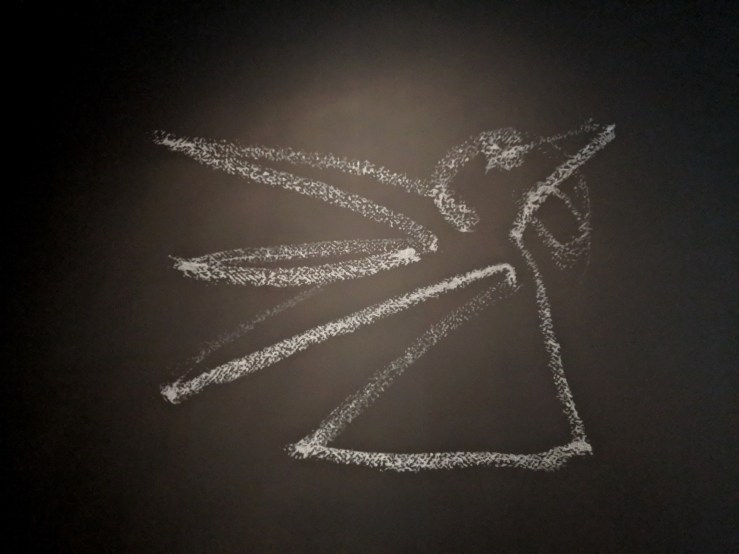

John Cage

Fontana Mix, 1958

Ink on paper and transparent sheets

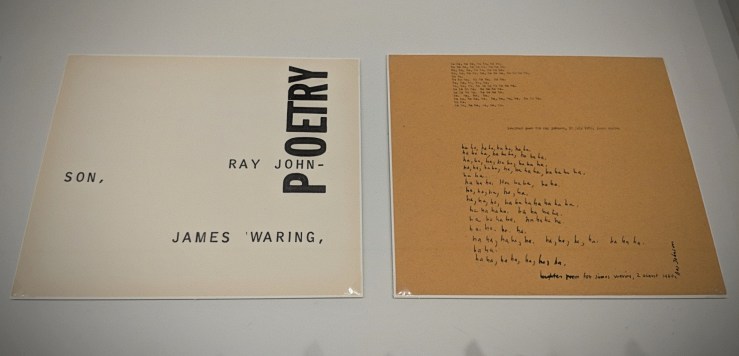

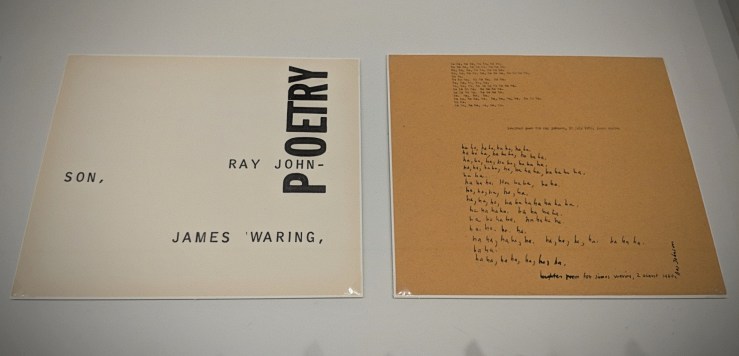

Laughter poem* for James Waring, 2 August 1960, by Ray Johnson

Laughter poem* for James Waring, 2 August 1960, by Ray Johnson

*If you are curious to know how a laughter poem sounds, please click on this page: Atlanta Poets Group to find out. You can also listen to the first one: Laughter poem for Ray Johnson, 30 July 1960, by James Waring.

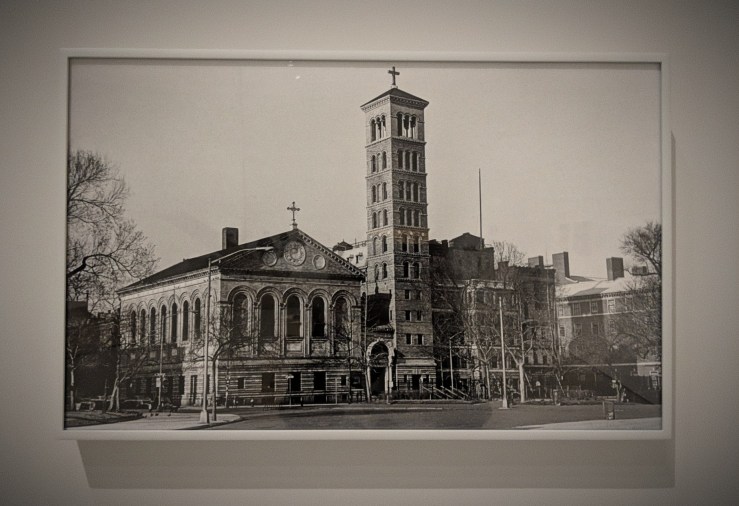

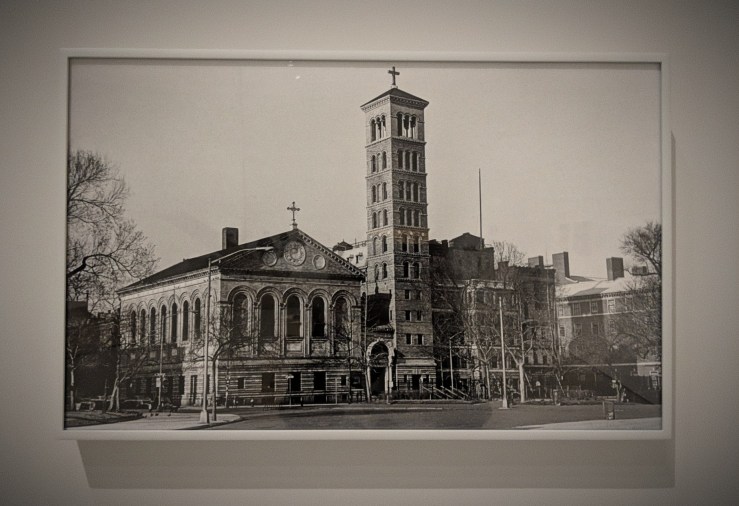

Judson Memorial Church, New York – March 16, 1966

Judson Memorial Church, New York – March 16, 1966

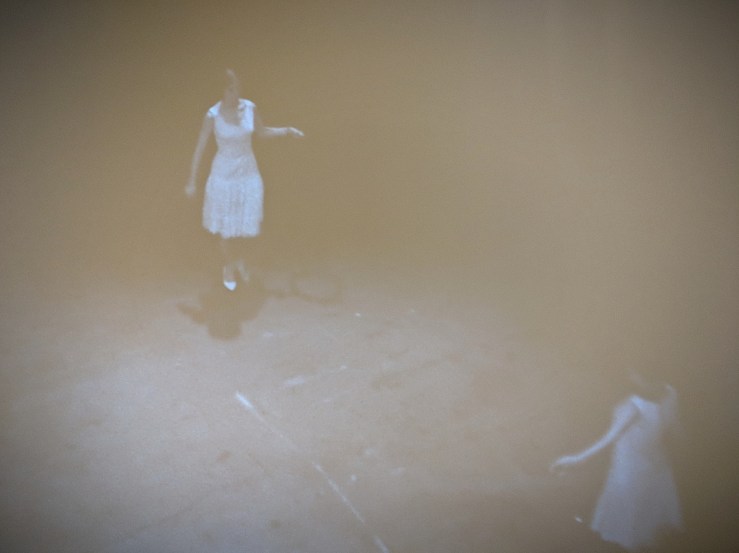

Fred W. McDarrah

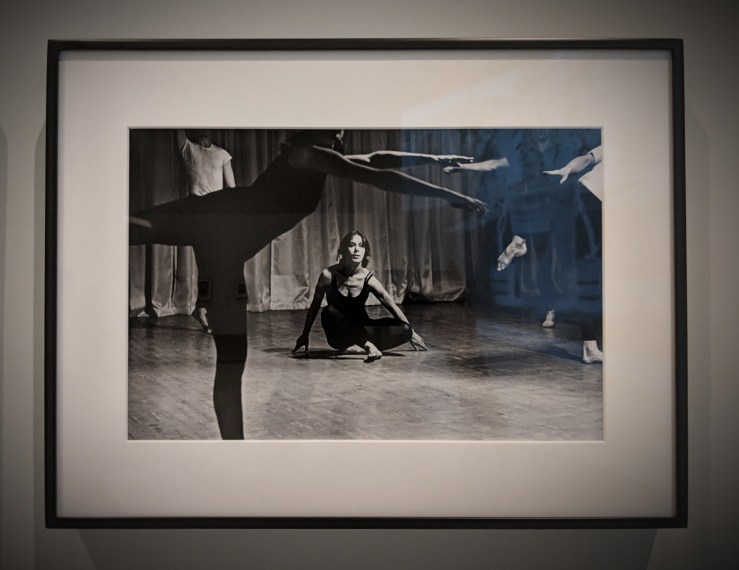

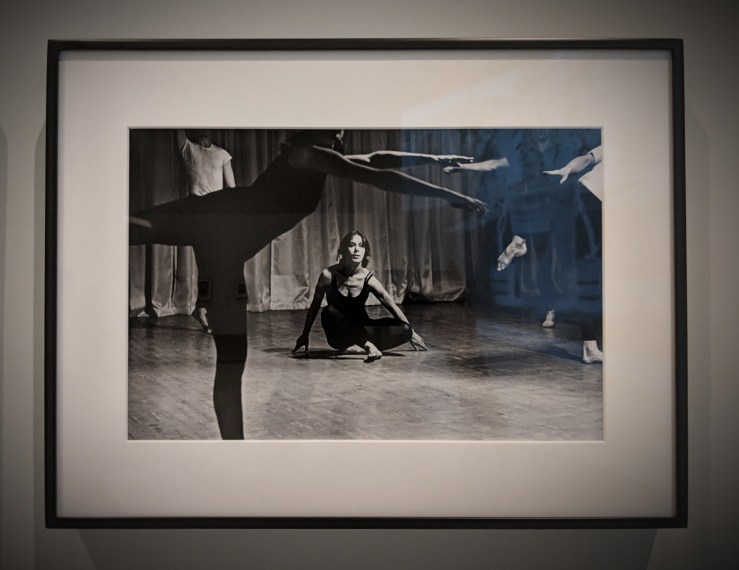

Yvone Rainer

Yvone Rainer

”Bach” From Terrain, 1963

Performed at Judson Memorial Church, April 28th, 1963

By Trisha Brown, William Davis, Judith Dunn, Steve Paxton, Yvonne Rainer and Albert Reid

Rainer’s first evening-length work Terrain, was a five-part dance for multiple performers. Some of the sections were choreographed, while others were structured like a game, with rules and strategies that defined each dancer’s behavior but still allowed for spontaneity and improvisation.

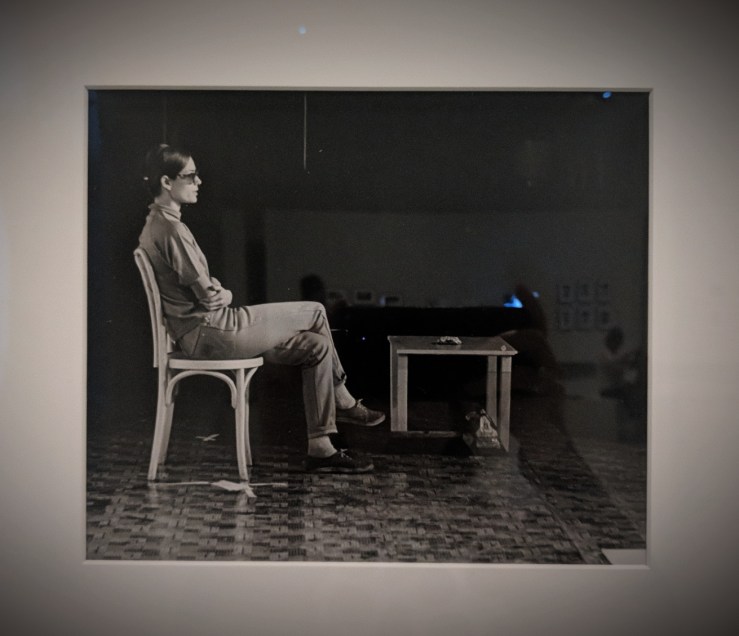

Lucinda Childs

Geranium, 1965. Performed at 940 Broadway, January 29th, 1965

Geranium was set to the sounds of a championship football game, complete with sports commentators describing the action on the field, to which Childs added her imitation of sports broadcasting and intervals of music. Using the tape as a score and its sounds as cues, Childs interacted with objects including a wooden pole, a tinfoil scrap, a hammer and a pound of soil. She used a hammock to support her weight as she performed, in slow motion, the movement of a football player who – according to the broadcast – raced toward the ball, stumbled and fell.

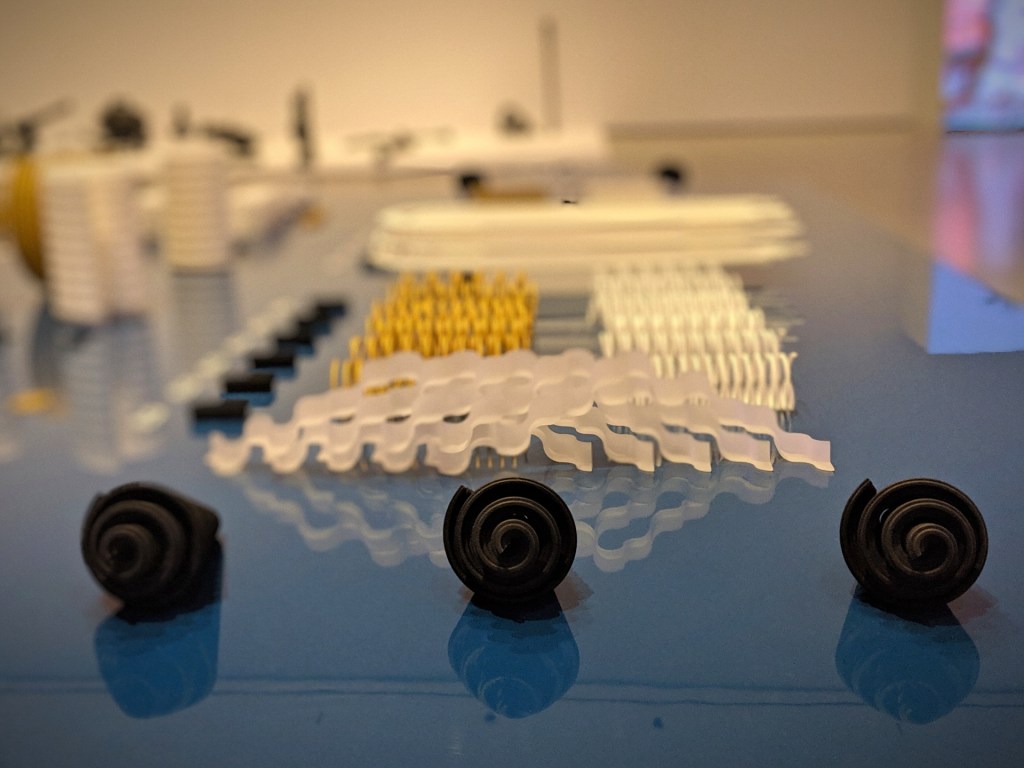

Huddle is part of Simone Forti’s Dance Constructions (1960-61), a continually shifting mass of bodies. Seven to nine performers create a solid base and take turns climbing over the group. In doing this, they create a sculptural form Forti has often described as a mountain.

Simone Forti’s Dance Constructions (1960–61) were key forerunners to Judson Dance Theater. Made from inexpensive materials, including plywood and rope, each “construction” prompts actions such as climbing, leaning, standing or whistling. Simultaneously sculptures and performances, the works were first presented at Reuben Gallery and the artist Yoko Ono’s loft, both in New York.

Huddle was performed live in intervals, throughout the exhibition.

September 15th, 2018