Elegance, about 1927 – marble

Heinz Warneke

National Portrait Gallery, Washington, D.C.

March 22nd, 2019

Elegance, about 1927 – marble

Heinz Warneke

National Portrait Gallery, Washington, D.C.

March 22nd, 2019

The industrial lines within the National Portrait Gallery, paired to perfection with the outlines of the United States on

Electronic Superhighway: Continental U.S., Alaska, Hawaii, 1995-96

forty-nine-channel closed-circuit video installation, neon, steel, and electronic components

by Nam June Paik

Electronic Superhighway is Nam June Paik’s tribute to the United States, his adopted homeland. Paik, born in Korea in 1932, moved to New York in 1964 and lived in America until his death in 2006.

Though the outlines of the fifty states are familiar, Electronic Superhighway challenges the viewer to look with new eyes at the cultural map of the United States. Each state is represented by video footage reflecting the artist’s personal, and often unexpected connections to his artistic friends – composer John Cage in Massachusetts, performance artist Charlotte Moorman in Arkansas, and choreographer Merce Cunningham in Washington. Some states he knew best through classic movies – The Wizard of Oz appears for Kansas, Showboat for Mississippi, and South Pacific for Hawaii. Sometimes he chose video clips or assembled flickering slideshows that evoke familiar associations, such as the Kentucky Derby, Arizona highways, and presidential candidates campaigning in Iowa. Topical events such as the fires of the 1993 Waco siege or Atlanta’s 1996 summer Olympics create portraits of moments in time. Old black-and-white television footage and audio of Martin Luther King’s speeches recall Civil Rights struggles in Alabama. California has the fastest-paced imagery: racing through the Golden Gate Bridge, the zeros and ones of the digital revolution, and a fitness class led by O.J. Simpson. A mini-cam captures images of Superhighway’s viewers and transmits those images to a tiny screen representing Washington, D.C. making visitors a part of the story.

Nam June Paik is hailed as the ”father of video art” and credited with the first use of the term ”information superhighway” in the 1970s. He recognized the potential for media collaboration among people in all parts of the world, and he knew that media would completely transform our lives. Electronic Superhighway – constructed of 336 televisions, 50 DVD players, 3.750 feet of cable, and 575 feet of multicoloured neon tubing – is a testament to the ways media defined one man’s understanding of a diverse nation.

National Portrait Gallery, Washington, D.C.

March 22nd, 2019

National Portrait Gallery, Washington, D.C.

March 22nd, 2019

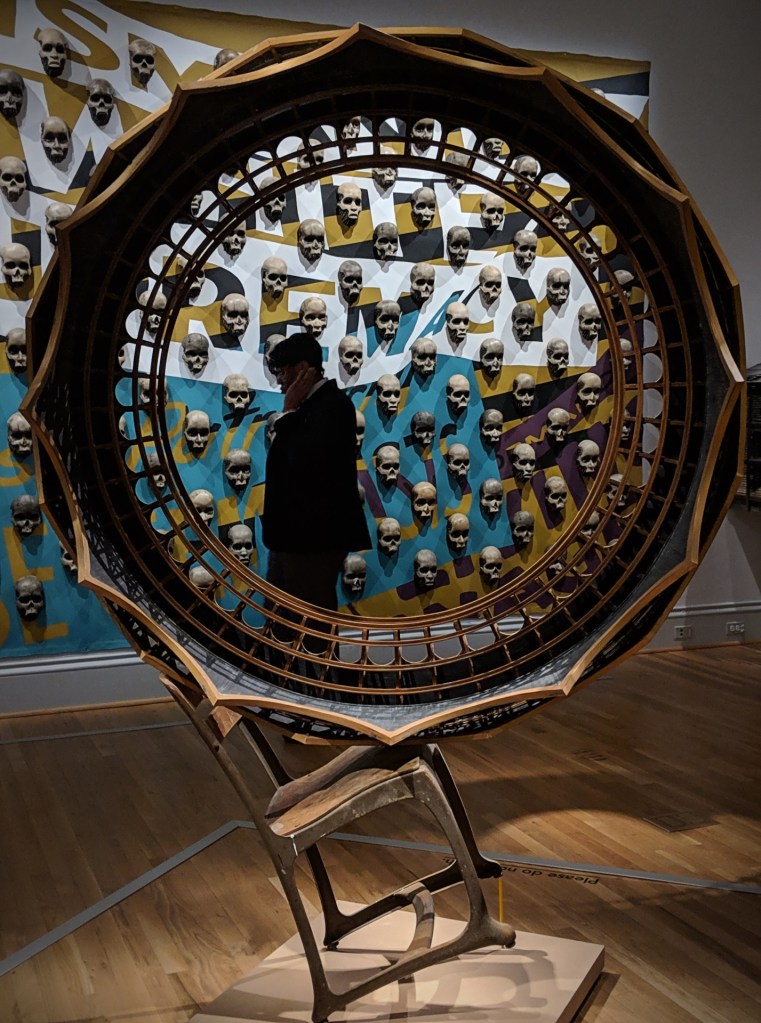

Tomb II

Gregory Gillespie, 1936-2000

Gillespie was thinking about the conventions surrounding death when he made this sculpture. He told and interviewer in 1999, ”I want this big tomb at my wake. It will add some humour to the event. But it’s really a kind of joke because it’s so big and bright and funny that I don’t think people are really going to … have it here.” And yet, it was there.

Self-Portrait

Mixed media on wood panels, 1998-1999

At the National Portrait Gallery, Washington, D.C.

March 22nd, 2019

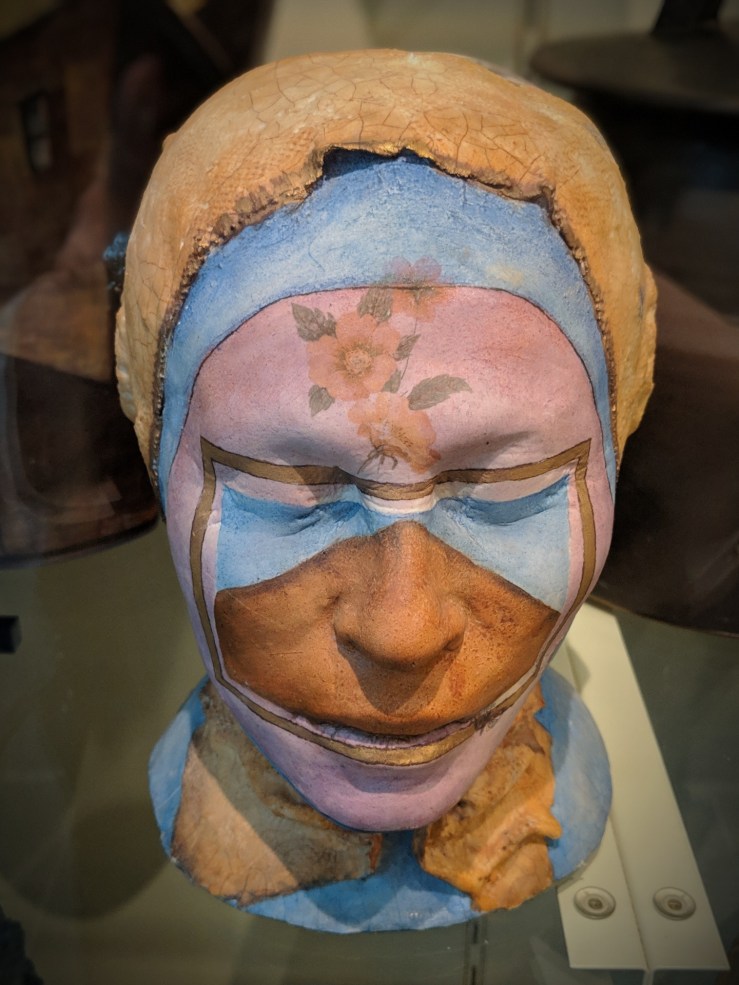

The Reconstruction Of Saints – 2018 – Aquaresin, fiberglass, foam, plywood, 24k gold

From ”Disrupting Craft: Renwick Invitational 2018” presenting work from four artists: Tanya Aguiñiga, Sharif Bey, Dustin Farnsworth and Stepanie Syjuco.

March 22nd, 2019

In this installation, Syjuco’s contemporary “still life” takes as inspiration the subjects of photographic color calibration charts that have been long used to check for “correct” or “neutral” color. The array of images and objects in the works creates a visual friction, challenging the idea of cultural and political neutrality by presenting a coded narrative of empire and colonialism as told through art history, Modernism, ethnography, stock photos, and Google Image searches. [source: Stephanie Syjuco]

From ”Disrupting Craft: Renwick Invitational 2018” presenting work from four artists: Tanya Aguiñiga, Sharif Bey, Dustin Farnsworth and Stepanie Syjuco.

March 22nd, 2019

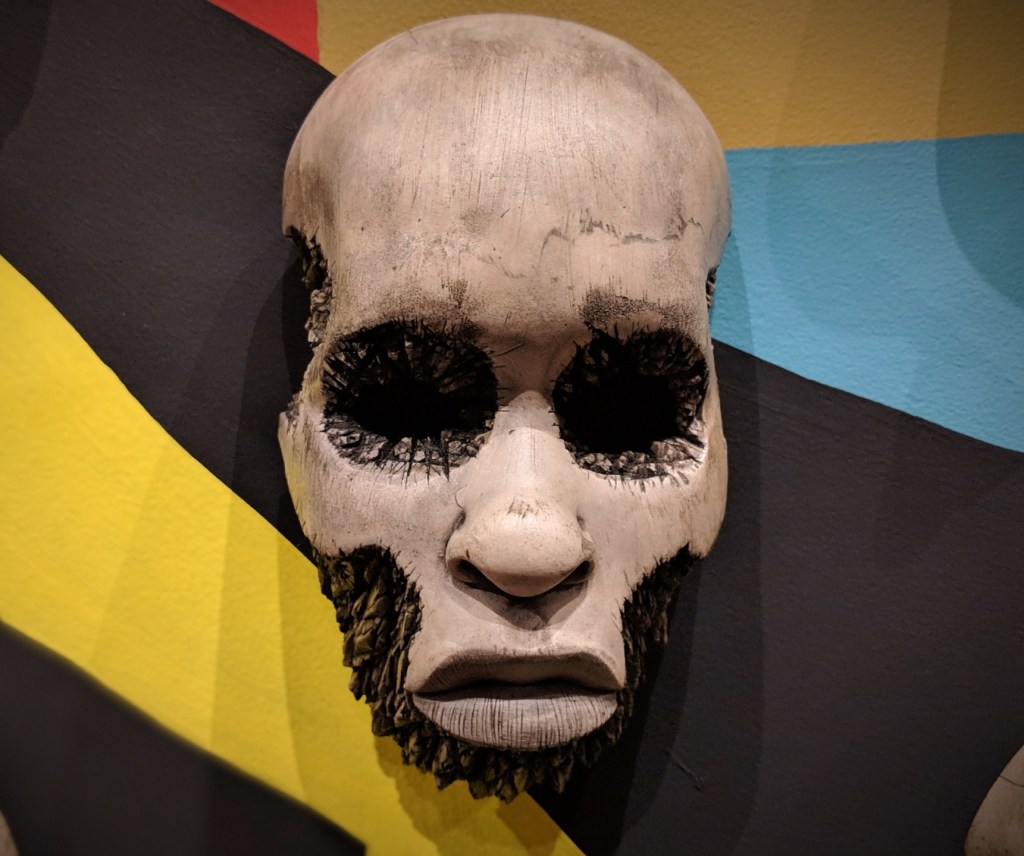

All artwork by Dustin Farnsworth

From ”Disrupting Craft: Renwick Invitational 2018” presenting work from four artists: Tanya Aguiñiga, Sharif Bey, Dustin Farnsworth and Stepanie Syjuco.

March 22nd, 2019

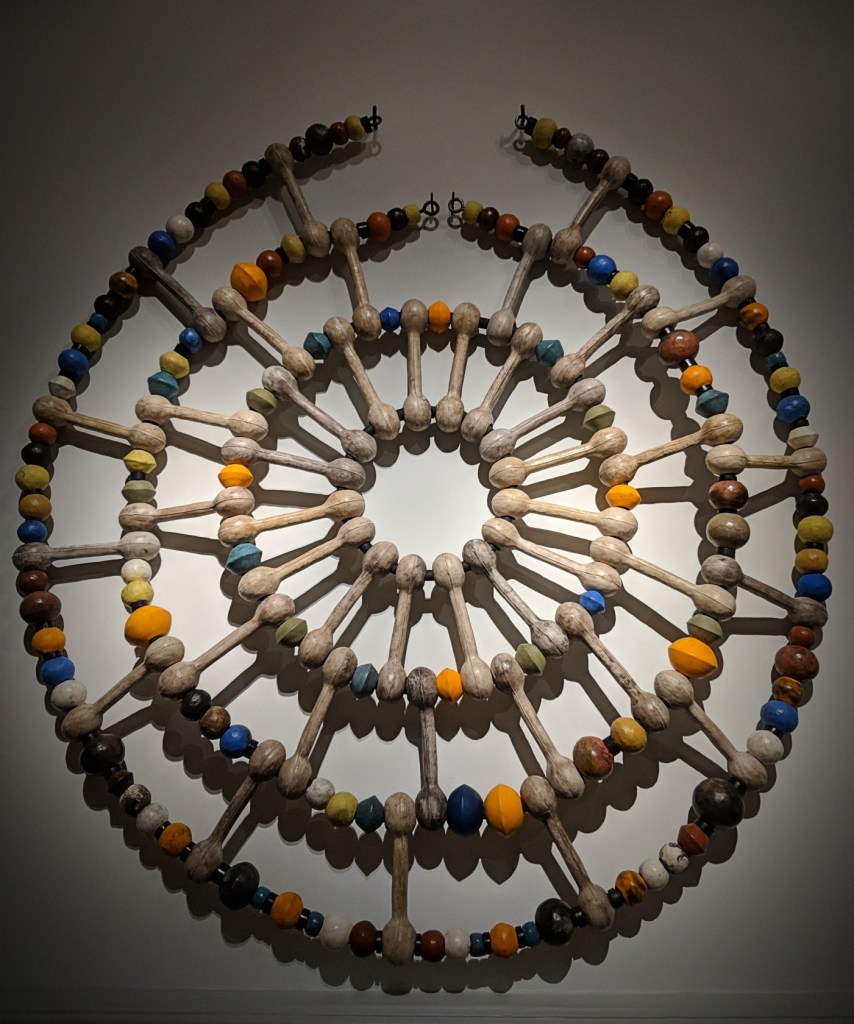

by Sharif Bey

Assimilation?

Destruction?

2000

terracotta

”A mass of disembodied ceramic human heads randomly piled onto the floor […]. The viewer is confronted by the bald figures, all with a slightly different physiognomy and in the different shades of human skin—brown and black, and occasionally, white. The assemblage by ceramicist Sharif Bey, titled Assimilation? Destruction? is primarily about globalization and cultural identity. It is also a reference to Bey’s identity as a potter and an artist of color.”

”The piece is never the same in any exhibition—the 1,000 or so pinch pot heads are brought to a gallery in garbage cans and “unceremoniously dumped out,” says Bey, showing a video of the process. The heads break, crack and get pounded into smaller shards. Over time, he says, the piece, which he created for his MFA thesis project in 2000, will become sand. Ultimately, Assimilation? Destruction? signifies that “you’re everything and you’re nothing at the same time.” With its shifting collective and individual shapes, the assemblage is also “a comment on what it means to be a transient person,” he says.” [source: Smithsonian Magazine]

From ”Disrupting Craft: Renwick Invitational 2018” presenting work from four artists: Tanya Aguiñiga, Sharif Bey, Dustin Farnsworth and Stepanie Syjuco.

March 22nd, 2019

Created as a response to the tragic amount of school shootings in the United States and the Boko Haram abductions of Nigerian schoolgirls in 2014, these skull-like masks represent children’s faces.

This choker’s beads consists of nineteen nearly identical skulls carved from conch shells. The deeply carved eye sockets may have originally held hematite inlays. Young nobles who were being schooled in religion and military arts wore such necklaces throughout the Central Mexican Highlands.

Images from ”Disrupting Craft: Renwick Invitational 2018” presenting work from four artists: Tanya Aguiñiga, Sharif Bey, Dustin Farnsworth and Stepanie Syjuco, paired with a choker with Nineteen Death Heads, from Mexico from the Library of Congress.

March 22nd, 2019

Big enough for two

Palapa, 2017 by Tanya Aguiñiga

Powder-coated steel and synthetic hair

Named for the open-sided thatched huts that pepper the beaches of Mexico. These distinctive shelters are woven by Mexicans but used mostly by tourists. Aguiñiga’s mysterious, surreal interpretation of these everyday structures is symbolic of her own ambiguous identity, as someone who navigates the dual worlds of palapa maker and user, of and outside both cultures.

Smithsonian American Art Museum

Renwick Gallery

Washington, D.C.

March 22nd, 2019

subjective worldview

Actor, writer, cook and author

Travel experiences & Strasbourg city guide

Writer

joy, happiness, travel, adventure, gratitude

"Rêve onirique & Bulle d'évasion"

makes pretty things on paper

This WordPress.com site is Pacific War era information

Welcome to my curious world of words....

Photographs, music and writing about daily life. Contact: elcheo@swcp.com

Free listening and free download (mp3) chill and down tempo music (album compilation ep single) for free (usually name your price). Full merged styles: trip-hop electro chill-hop instrumental hip-hop ambient lo-fi boombap beatmaking turntablism indie psy dub step d'n'b reggae wave sainte-pop rock alternative cinematic organic classical world jazz soul groove funk balkan .... Discover lots of underground and emerging artists from around the world.

A 365 analogue photography project

Barcelona's Multiverse | Art | Culture | Science

Een digitaal atelier aan de (zee)slag.

‘Doodling Ambiguity’s in Ink.’

Miscellaneous photography

Glimpses along the way on a journey of discovery into symmetry...