In 2017, MoMA – jointly with Columbia University – acquired the vast archives of Frank Lloyd Wright, one of the most prolific architects of the 20th century. To mark that acquisition, as well as the 150th anniversary of his birth on June 8, 1867, MoMA presented Frank Lloyd Wright at 150: Unpacking the Archive, an exhibition that comprised some 450 works made from the 1890s through the 1950s and included architectural drawings, models, building fragments, films, print media, furniture, tableware, textiles, paintings, photographs, and scrapbooks. According to its curator, Barry Bergdoll, the show was meant “to announce that Frank Lloyd Wright is open to new interpretations” and that “the archive is here and it’s open.”

Having had a closer look on Mr. Wright’s incredibly detailed, delicate, at once artistically accomplished and architecturally precise designs, I can attest to the show’s success in opening the work of one of America’s – and the world’s – greatest architects, to new interpretations. At least to my, not-so-expert, eyes.

Goron Strong Automobile Objective and Planetarium, Sugarloaf Mountain, Maryland

Goron Strong Automobile Objective and Planetarium, Sugarloaf Mountain, Maryland

Project, 1924-25 // Pencil and coloured pencil on tracing paper

This project is often seen as a forerunner of the Guggenheim Museum, built two decades later.

Fallingwater (Kaufmann House), Mill Run, Pennsylvania 1934-37

Fallingwater (Kaufmann House), Mill Run, Pennsylvania 1934-37

Pencil and coloured pencil on paper

The bold design of a house over a waterfall for Pittsburgh department store magnate Edgar Kaufmann put Wright back in the public eye at a moment when he was increasingly anxious that his fame had faded. This drawing landed Wright on the cover of Time magazine in 1938 – he was only the third architect ever to receive that honour – and was also displayed that same year in an exhibition at MoMA devoted solely to his unprecedented house design.

Moore House, Oak Park, Illinois, 1895

Moore House, Oak Park, Illinois, 1895

Ink on paper

Madison Civic Center (Monona Terrace), Madison, Wisconsin

Madison Civic Center (Monona Terrace), Madison, Wisconsin

Project, 1938-59 // Ink and pencil on paper mounted on plywood

Even as Wright reimagined Chicago as a city dominated by a few super-tall skyscrapers but otherwise given over to a prairie landscape, he also designed urban projects – many of the megastructures, such as this one for Monona Terrace, which integrated transportation and infrastructure with public and commercial programmes – with the intention of revitalizing urban cores and engaging the preexisting city and its surroundings. This project was realized decades after Wright’s death.

The Mile-High Illinois, Chicago

The Mile-High Illinois, Chicago

Project, 1956 // Pencil, coloured pencil and gold ink on tracing paper

In this perspective drawing, Wright inserts his imagined mile-high skyscraper into the lakefront area of Chicago, which he transforms into a green landscape, rendering obsolete many of the city’s older, densely packed towers. The Mile-High becomes a singular object, in dialogue only with another Wright proposal: a tower called the Golden Beacon, visible in the background.

Plan for Greater Baghdad

Plan for Greater Baghdad

Project, 1957 // Ink, pencil and coloured pencil on tracing paper

In 1957, Wright, along with a number of ”starchitects” including Alvar Aalto, Le Corbusier and Walter Gropius, was commissioned to design a signature building in Baghdad as part of an Iraqi government programme to bring Western architecture to the capital city. Although asked only to design an opera house, Wright expanded the programme into an entire cultural centre – including a university, two museums, a zoo and various recreational facilities – and moved the site to an island in the Tigris River. Wright’s project, like most of the others, was cancelled after the revolution of 1958.

Butterfly Wing Bridge, San Francisco

Butterfly Wing Bridge, San Francisco

Project, 1949-53 // Ink, pencil and coloured pencil on tracing paper

Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York 1943-59

Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York 1943-59

Gouache on paper mounted on board

American System-Built Houses for the Richards Company

American System-Built Houses for the Richards Company

Project 1915-17

Bogk House, Milwaukee, Wisconsin – 1916-17

Bogk House, Milwaukee, Wisconsin – 1916-17

Watercolour, gouache, gold paint and graphite on paper mounted on Japanese paper

The two winged figures depicted in this sculptural frieze for the Bogk House recall, in their blocky, geometric forms, Mayan and Aztec motifs, while their wings resemble the eagle imagery prominent in the Pueblo Eagle Dance. The Eagle Dance was one of the most popular ceremonial dances performed at the 1915 Panama-California Exposition in San Diego, which Wright attended and where he encountered theories positing that contemporary American Indians were descendants of a venerable, ancient American civilization.

Lake Tahoe Resort, Lake Tahoe, California

Lake Tahoe Resort, Lake Tahoe, California

Project, 1923-24 // Pencil and coloured pencil on tracing paper

Eugene Masselink (1910-1962)

Eugene Masselink (1910-1962)

Pattern studies // Pencil and coloured pencil on paper

Various cacti, rock formations and lichen are distilled into their essential organizing forms in these applied pattern studies, demonstrating the generative relationship between nature and architecture in Wright’s practice. According to Wright, the cellular structure of desert plants, for example, offered lessons in economical construction. Believing the artist should approximate nature through a process of conventionalization or abstraction – seeking underlying geometries rather than outward forms – Wright incorporated such pattern studies into his educational approach at the Taliesin Fellowship. Eugene Masselink, one of Wright’s most talented apprentices, drew these examples.

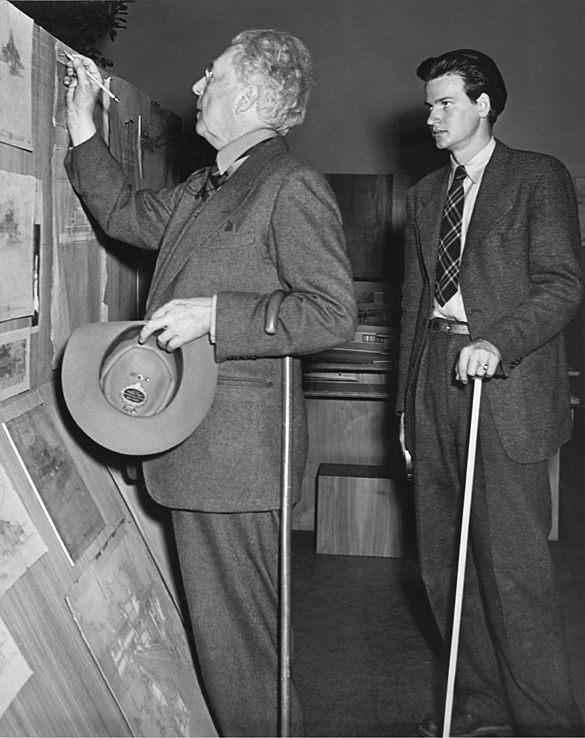

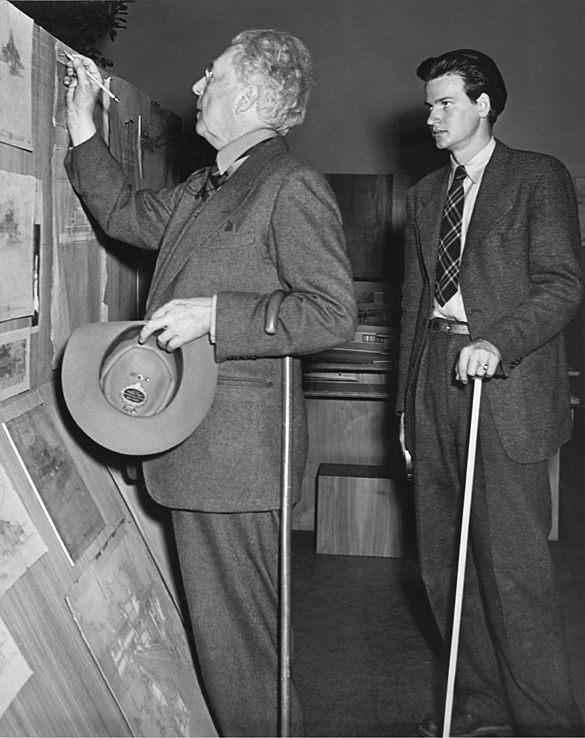

Frank Lloyd Wright and his assistant Eugene Masselink installing the exhibition Frank Lloyd Wright: American Architect at The Museum of Modern Art, November 13, 1940-January 5, 1941. Photographic Archive. The Museum of Modern Art Archives, New York

Frank Lloyd Wright and his assistant Eugene Masselink installing the exhibition Frank Lloyd Wright: American Architect at The Museum of Modern Art, November 13, 1940-January 5, 1941. Photographic Archive. The Museum of Modern Art Archives, New York

Photo: Soichi Sunami

Preliminary scheme for Imperial Hotel, Tokyo 1913-23

Preliminary scheme for Imperial Hotel, Tokyo 1913-23

Ink and pencil on drafting cloth

The Imperial Hotel in Tokyo took over a decade to build and exerted a profound influence on both Wright’s designs and the architecture of a modernizing Japan.

Having survived the Great Kantō Earthquake in 1923 and the American bombing of the city during World War II, it was finally demolished in 1968 to be replaced with a modern hotel tower.

Portions of the Imperial Hotel, including the grand entrance/lobby and the reflecting pool, were saved and painstakingly relocated to the Meiji Mura Museum, an open-air architectural theme park in Inuyama that contains more than 60 historic, culturally significant buildings from Japan and beyond. [source]

March Balloons, 1955

March Balloons, 1955

Drawing based on a cover design for Liberty magazine, c. 1926

From Frank Lloyd Wright at 150: Unpacking the Archive, an exhibition that ran through October 1st, 2017 at MoMA.

September 25th, 2017

Goron Strong Automobile Objective and Planetarium, Sugarloaf Mountain, Maryland

Goron Strong Automobile Objective and Planetarium, Sugarloaf Mountain, Maryland Fallingwater (Kaufmann House), Mill Run, Pennsylvania 1934-37

Fallingwater (Kaufmann House), Mill Run, Pennsylvania 1934-37 Moore House, Oak Park, Illinois, 1895

Moore House, Oak Park, Illinois, 1895 Madison Civic Center (Monona Terrace), Madison, Wisconsin

Madison Civic Center (Monona Terrace), Madison, Wisconsin The Mile-High Illinois, Chicago

The Mile-High Illinois, Chicago Plan for Greater Baghdad

Plan for Greater Baghdad Butterfly Wing Bridge, San Francisco

Butterfly Wing Bridge, San Francisco

Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York 1943-59

Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York 1943-59 American System-Built Houses for the Richards Company

American System-Built Houses for the Richards Company

Bogk House, Milwaukee, Wisconsin – 1916-17

Bogk House, Milwaukee, Wisconsin – 1916-17 Lake Tahoe Resort, Lake Tahoe, California

Lake Tahoe Resort, Lake Tahoe, California

Eugene Masselink (1910-1962)

Eugene Masselink (1910-1962) Frank Lloyd Wright and his assistant Eugene Masselink installing the exhibition Frank Lloyd Wright: American Architect at The Museum of Modern Art, November 13, 1940-January 5, 1941. Photographic Archive. The Museum of Modern Art Archives, New York

Frank Lloyd Wright and his assistant Eugene Masselink installing the exhibition Frank Lloyd Wright: American Architect at The Museum of Modern Art, November 13, 1940-January 5, 1941. Photographic Archive. The Museum of Modern Art Archives, New York Preliminary scheme for Imperial Hotel, Tokyo 1913-23

Preliminary scheme for Imperial Hotel, Tokyo 1913-23

March Balloons, 1955

March Balloons, 1955